The actual facts of the matter are hard to come by. I began here:

‘You are right. I understood this myself when I read your novel The Time Machine. All human conceptions are on the scale of our planet. They are based on the pretension that the technical potential, though it will develop, will never exceed the terrestrial limit. If we succeed in establishing interplanetary communications, all our philosophies, moral and social views, will have to be revised. In this case the technical potential, become limitless, will impose the end of the role of violence as a means and method of progress.’

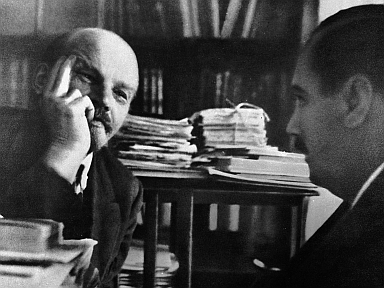

— Vladimir Ilych Lenin, in conversation with H. G. Wells

SOURCE: Roberts, Adam. Yellow Blue Tibia (London: Gollancz, 2009), epigraph to this science fiction novel.

And then to here:

‘Lenin told the British science fiction writer, H.G. Wells, who interviewed him in the Kremlin in 1920, that if life were discovered on other planets, revolutionary violence would no longer be necessary: “Human ideas — he told Wells — are based on the scale of the planet we live in. They are based on the assumption that the technical potentialities, as they develop, will never overstep ‘the earthly limit.’ If we succeed in making contact with the other planets, all our philosophical, social and moral ideas will have to be revised, and in this event these potentialities will become limitless and will put an end to violence as a necessary means of progress.”

SOURCE: Stites, Richard. Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Vision and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989) p. 42. From chapter 2: “Revolution: Utopias in the Air and on the Ground,” section “The Dreamer in the Kremlin,” pp. 41-46. This quote can be found here: Lenin / H.G. Wells.

The source is given in footnote 13, p. 263:

13. The first quotation is from Patrick McGuire, Red Stars: Political Aspects of Soviet Science Fiction (Ann Arbor: UMI, 1985) 122, n. 39; the second from Striedter, “Journeys,” 36 . Lenin’s library contained Bogdanov’s Engineer Menni and many of his nonfiction works, the works of Bryusev, Mayakovsky , and Klyuev (see Chapter 9); Nikolai Morozov’s Star Songs, Ilya Ehrenburg’s Julio Jurenito and Trust DE (two anti-capitalist political fantasies), and the monarchist utopian novel Beyond the Thistle by Peter Krasnov (see Chapter 8): Biblioteka V. I. Lenina v Kremle: katalog (Moscow: Vsesoyuznaya palata, 1961). Absent from the collection are Chernyshevsky’s What Is To Be Done? and Bogdanov’s Red Star (both of which he had read). Lenin must have read Wells’s Time Machine just prior to the interview since he told the sculptress Clare Sheridan in 1920 that regretfully he had read none of Wells’s science fiction: Russian Portraits (London: Cape, 1921) 108.

Before tracing this further, I jumped to the following book and found this:

SOURCE: Kozyreva, Maria; Shamina, Vera. “Russia Revisited,” in The Reception of H. G. Wells in Europe, edited by Patrick Parrinder & John S. Partington (London: Thoemmes Continuum, 2005), pp. 48-62. See: “Wells’s second visit, 1920,” p. 53:

But of course the main event of his second visit to Russia was his meeting with Lenin in Moscow on 6 October. It is strange that for a long time the exact date of the meeting was uncertain and that no notes were taken of what was said. Even the person accompanying Wells, F. Rootstein, spoke about the meeting in general terms and dated it to 1918. The only sources, therefore, are Wells himself and Claire Sheridan, the British sculptor who was working on Lenin’s bust while Wells was in Moscow. When she talked to Lenin about Wells, the Soviet leader said he had read only one of his novels (Kagarlitsky 1970, 244).

The reference:

Kagarlitsky, Julius (1970) ‘Chital li Lenin Wellsa’, Voprosy literatury [Moscow], 10: 244.

Here is what Claire Sheridan wrote, based on her conversation with Lenin:

We talked about H. G. (Wells) and he said the only book of his he had read was “Joan and Peter,” but that he had not read it to the end. He liked the description at the beginning of the English intellectual bourgeois life. He admitted that he should have read, and regretted not having read some of the earlier fantastic novels about wars in the air, and the world set free.

SOURCE: Sheridan, Claire. Mayfair to Moscow: Clare Sheridan’s Diary (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1921), p. 117. Also published as: Russian Portraits. London: J. Cape, 1921. Also available via HathiTrust.

McGuire cites Kagarlitski. Wells’s own account of his discussion with Lenin, if cited accurately, looks implausible.

39. Besides several extant comments on Bogdanov’s science fiction, Lenin is remembered as having discussed science fiction or interplanetary travel on several occasions. According to H.G. Wells, Lenin said in 1920 “that as he read The Time Machine he understood that human ideas are based on the scale of the planet we live in: They are based on the assumption that the technical potentialities, as they develop, will never overstep ‘the earthly limit.’ If we succeed in making contact with the other planets, all our philosophical, social and moral ideas will have to be revised, and in this event these potentialities will become limitless and will put an end to violence as a necessary means to progress” (J. Kagarlitski, The Life and Thought of H.G. Wells, trans. Moura Budberg [London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1966], p. 46. Budberg probably retranslated from the Russian. Elsewhere, Soviet critics cite E. Drabkina, “Nevozmoshnogo net,” Izvestiia, 22 December 1961, p. 4, for this quotation. Drabkina in turn refers to an unspecified issue of Le Paris-Presse, apparently for 1959,) Lenin’s personal library in the Kremlin included only two works of science fiction (Bogdanov’s Engineer Menni and Morozov’s collection of science-fiction poetry, Star Songs), and no nonfiction speculations on interplanetary travel (Biblioteka V.I. Lenina v Kremle [Moscow: lzd. Vsesoiuznoi knizhnoi palati, 1961]).

SOURCE: McGuire, Patrick. Red Stars: Political Aspects of Soviet Science Fiction (Ann Arbor: UMI, 1985) p. 122, note 39.

The trail leads here:

Not even the author of The Time Machine himself realized the enormous possibilities implicit in this outlook. In 1920, after a conversation with Lenin, Wells made a note, which was published fairly recently—after the Soviet flight to the moon. “Lenin said”, wrote Wells, “that as he read The Time Machine he understood that human ideas are based on the scale of the planet we live in: they are based on the assumption that the technical potentialities, as they develop, will never overstep ‘the earthly limit’. If we succeed in making contact with the other planets, all our philosophical, social and moral ideas will have to be revised, and in this event these potentialities will become limitless and will put an end to violence as a necessary means to progress.”

SOURCE: Kagarlitski, J[ulius]. The Life and Thought of H. G. Wells, translated from the Russian by Moura Budberg (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1966), p. 46.

Here is where I first read about Wells’s meeting with Lenin, when I was laid up in bed with a long-term serious illness in early 1974: here is the editor’s prefatory note:

11. V. I. Lenin

The high point of Wells’s visit to Russia in 1920 was his audience with Lenin; in his book on the Russian trip, he calls this chapter “The Dreamer in the Kremlin.” After Wells left, Lenin is supposed to have exclaimed “What a bourgeois he is! He is a Philistine!” And then, says Trotsky, he “raised both hands above the table, laughed and sighed, as was characteristic of him when he felt a kind of inner shame for another man.” *

* Leon Trotsky, Lenin (New York, 1925), p. 173.

SOURCE: Wells, H. G. Journalism and Prophecy, 1893-1946: An Anthology, compiled and edited by W. Warren Wagar (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1964), p. 329. Prefatory note to II: Portraits: 11. V. I. Lenin, pp. 329-336. The original source for this portrait is Wells’s Russia in the Shadows, pp. 145-50, 152-67.

The dreamer in the Kremlin | The Charnel-House

H. G. Wells Interviews Vladimir Lenin, 1920 (Grasping Reality with Both Hands: bradford-delong.com; blog)

Forgotten October: H.G. Wells interview of Lenin (Rick Searle, Utopia or Dystopia, blog)

Roberts, Adam. Russia in the Shadows (1921), Wells at the World's End (blog), 26 November 2017.

Timofeychev, Alexey. Surprised by Russia: How Lenin and Stalin astonished H. G. Wells, Russia Beyond, April 18, 2018.

Wells, H. G. “It seems to me that I am more to the Left than you, Mr Stalin” (interview), The New Statesman, originally special NS supplement, 27 October 1934.

Wells, H. G. Russia in the Shadows. Hodder & Stoughton, Ltd., London, 1920.

Leon Trotsky on H. G. Wells as Philistine

Chapter

2 of The Life and Thought of H.G. Wells: Between the Past and the Future:

[On The Time Machine]

by Julius Kagarlitski, translated from the Russian

by Moura Budberg

Journalism

and Prophecy, 1893-1946: An Anthology,

by H. G. Wells, compiled & edited by W. Warren Wagar

Chapter

VII: The Conflict of Languages

from Anticipations by H. G. Wells

[Paradoxes

of Time Travel] From “Without Prejudice”

by Israel Zangwill

The Definitive Time Machine: A Critical Edition of H.G. Wells’s Scientific Romance

Red Stars: Political Aspects of Soviet Science Fiction by Patrick McGuire

Dystopia

west, dystopia east: the vanishing of speculative fiction under Stalinism

by Erika Gottlieb

The Life and Thought of H.G. Wells by Julius Kagarlitski

Mankind and the Year 2000 by V. Kosolapov

Universal Language in Soviet Science Fiction by Patrick McGuire

Yevgeny Zamyatin on Revolution, Entropy, Dogma and Heresy

H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine: Selected Bibliography

Science Fiction

& Utopia Research Resources:

A Selective Work in Progress

Salvaging Soviet Philosophy (1)

H. G. Wells Revisited (2): Wells & Borges

Home Page | Site

Map | What's New | Coming Attractions | Book

News

Bibliography | Mini-Bibliographies | Study

Guides | Special Sections

My Writings | Other Authors' Texts | Philosophical

Quotations

Blogs | Images

& Sounds | External Links

CONTACT Ralph Dumain

Uploaded 15 July 2018

Last update 28 June 2023

Previous update 18 March 2020

Photo added 21 April 2020

Site ©1999-2023 Ralph Dumain