Letter to Ludwig Feuerbach from Ottilie Assing

about Frederick Douglass

New York, 15 May 1871

My Dear Sir!

You may be amazed to be addressed from so great a distance by a person unknown

to you. I might not have had the courage did I not believe that any success

in your endeavors for the intellectual liberation of the human race must give

you something of the satisfaction which the Christian missionary experiences

when he, from his point of view has saved souls. I had always hoped to pay a

visit to Germany, after a long period of absence, and to meet you personally,

and although I have not abandoned this hope, so many obstacles are momentarily

in the way of fulfillment that I prefer to tell you in the form of a letter

what I had planned to talk to you about.

A number of years ago I met Frederick Douglass, a man whose name has possibly

reached you. He is a mulatto, was born a slave in the South, and gained his

freedom through flight to the North. Thanks to his exceptional talent, his skills

as a writer, and his brilliant rhetoric he worked his way out of obscurity within

a few years and became one of the most famous men in America. He was one of

the most superior among the anti-slavery agitators, and since the abolition

of slavery he excels no less by his discourse on political and social questions.

Personal sympathy and concordance in many central issues brought us together;

but there was one obstacle to a loving and lasting friendship�namely,

the personal Christian God. Early impressions, environments, and the beliefs

still dominating this entire nation held sway over Douglass. The ray of light

of German atheism had never reached him, while I, thanks to natural inclination,

training, and the whole influence of German education and literature, had overcome

the belief in God at an early age. I experienced this dualism as an unbearable

dissonance, and since I not only saw in Douglass the ability to recognize intellectual

shackles but also credited him with the courage and integrity to discard at

once the old errors and, in this one respect, his entire past, his lifelong

beliefs, I sought refuge with you. In the English translation by Mary Anne Evans

we read the Essence of Christianity together, which I, too, encountered

for the first time on that occasion. This book�for me one of the greatest manifestations

of the human spirit�resulted in a total reversal of his attitudes. Douglass

has become your enthusiastic admirer, and the result is a remarkable progress,

an expansion of his horizon, of all his attitudes as expressed especially in

his lectures and essays, which are intellectually much more rich, deep, and

logical than before. While most of his former companions in the struggle against

slavery have disappeared from the public stage since the abolition, and, in

a way, have become anachronisms because they lack fertile ideas, Douglass now

has reached the zenith of his development. For the satisfaction of seeing a

superior man won over for atheism, and through that to have gained a faithful,

valuable friend for myself, I feel obliged to you, and I cannot deny myself

the pleasure of expressing my gratitude as well as my heartfelt veneration.

Finally, I venture with typical American audacity to importune you with a request.

Would you be so kind as to grant me the pleasure of receiving a photograph of

you? I would ask you for two copies, one for me and one for Douglass. We as

atheists, who create no god to worship according to our image of ourselves,

are all the more attached in deep and ardent veneration to those human beings

in whom we recognize the representatives and translators of the highest ideas

of our age.

Your devoted

Ottilie Assing

SOURCE: Diedrich, Maria. Love

across Color Lines: Ottilie Assing and Frederick Douglass (New York:

Hill and Wang, 1999), pp. 259-260. Original German letter published in Ausgewälte

Briefe von und an Ludwig Feuerbach, ed. Hans-Martin Sass (Stuttgart: Friedrich

Frommann, 1964), vols. 12/13, pp. 365-366.

Diedrich describes the literary encounter with Feuerbach on pp. 227-230, taking

into account the history of Douglass's developing attitudes toward religion

and churches and Assing's probable exaggeration. On the German-American engagement

with Feuerbach and freethought, see pp. 113-114, 260-262, 288, also 328 for

Assing's visit to Europe. On the intellectual and literary world that Douglass

and Assing shared and Assing's fervent atheism, see pp. 190-192. On Douglass's

hostility to clerical hypocrisy, see also pp. 292-293. See also photos and captions

on pp. 225, 281, 353, 356.

See also:

Assing, Ottilie. Radical Passion: Ottilie Assing's Reports from America

and Letters to Frederick Douglass, edited, translated, and introduced by

Christoph Lohmann. New York: Peter Lang, 1999. (New Directions in German American

Studies; v. 1)

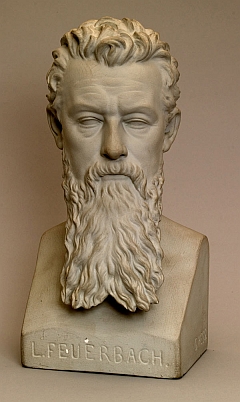

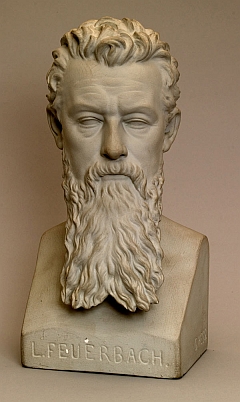

Bust

of Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872)

By G. Hess (1890s)

Feuerbach was a Young Hegelian philosopher,

a materialist & freethinker.

His book The Essence of Christianity

is in Mr. Douglass’ library.

Plaster. H 35.5 cm

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, FRDO 324

|

Courtesy National Park Service, Museum Management

Program & Frederick Douglass Historic Site

Frederick Douglass Photograph Catalog Number:

FRDO 3886

19.6 x 24.5 cm Photographer: Unknown

Frederick Douglass in his library,

which housed busts of Ludwig Feuerbach

and David Friedrich Strauss,

in his home at Cedar Hill, Washington DC

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site

Overview

Virtual

museum exhibit house tour

Library

Photos

of Douglass including study

|

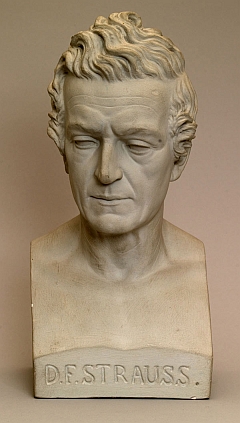

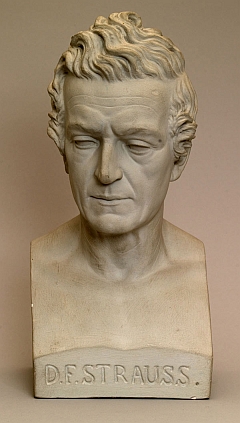

Bust

of David Strauss (1808-1874)

By G. Hess (1890s)

Strauss was a Hegelian philosopher,

German theologian of the higher criticism,

and the author of the Life of Jesus.

Plaster. H 34.5 cm

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site,

FRDO 325

|

Home of Frederick

Douglass, Cedar Hill, Washington, DC: Library:

Busts of David Friedrich Strauss & Ludwig Feuerbach

The

Index (A Weekly Paper), Volume 6, Whole no. 271, Thursday, March 4, 1875,

p. 1

(reports on George Hess et al)

Ludwig Feuerbach:

A Bibliography

The Young Hegelians:

Selected Bibliography

American Philosophy

Study Guide

The Afro-German

Connection: Web Guide & Bibliography

Black Studies, Music,

America vs Europe Study Guide

African American

/ Black Autodidacticism, Education, Intellectual Life (Bibliography in Progress)

Atheism / Freethought

/ Humanism / Rationalism / Skepticism / Unbelief / Secularism / Church-State

Separation Web Links

Home Page | Site

Map | What's New | Coming Attractions | Book

News

Bibliography | Mini-Bibliographies | Study

Guides | Special Sections

My Writings | Other Authors' Texts | Philosophical

Quotations

Blogs | Images

& Sounds | External Links

CONTACT Ralph Dumain

Uploaded 4 March 2002

Last update 6 April 2015

Previous update 30 March 2015

Site ©1999-2026 Ralph Dumain