It

is surely a remarkable success to which Dr. Zamenhof has attained. To

have given birth to an idea which has breathed a new hope into many despairing

hearts, to have created a language which, though it may never become universal,

is already spoken by hundreds of thousands of enthusiastic  disciples

in every part of the world; and to be the recipient of countless other

honours from distinguished public bodies, would be a wonderful achievement

in any case. But as the achievement of a Polish Jew, who has lived his

whole life in the heart of the Ghetto, working for his daily bread among

his poorer coreligionists as an eye-doctor, it is more wonderful still.

For the Jewish community, the progress of Dr. Zamenhof’s new language

will always possess a fascinating interest inasmuch as Esperanto owes

its existence to his strivings for the benefit of the Jewish race. It

was the protest of the warm-hearted Jew against the racial animosities

from which his people have been the principal sufferers. The invention

of a medium of international communication was intended to break down

the barriers of prejudice and misunderstanding that separate the families

of the human race from one another. It was one of the many movements

which the Jews of various countries and ages have led for the benefit

of mankind, and by which they have realised the ancient prophecy of becoming

disciples

in every part of the world; and to be the recipient of countless other

honours from distinguished public bodies, would be a wonderful achievement

in any case. But as the achievement of a Polish Jew, who has lived his

whole life in the heart of the Ghetto, working for his daily bread among

his poorer coreligionists as an eye-doctor, it is more wonderful still.

For the Jewish community, the progress of Dr. Zamenhof’s new language

will always possess a fascinating interest inasmuch as Esperanto owes

its existence to his strivings for the benefit of the Jewish race. It

was the protest of the warm-hearted Jew against the racial animosities

from which his people have been the principal sufferers. The invention

of a medium of international communication was intended to break down

the barriers of prejudice and misunderstanding that separate the families

of the human race from one another. It was one of the many movements

which the Jews of various countries and ages have led for the benefit

of mankind, and by which they have realised the ancient prophecy of becoming

A Blessing to others.

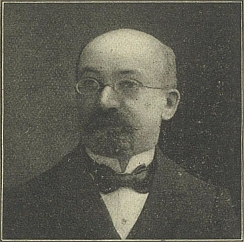

The success of this particular movement would be enough to turn the head of any ordinary man. But Dr. Zamenhof is not an ordinary man. He is so meek and modest—such an עניו, as they would say in the Ghetto—that through it all he has retained that simplicity of manner which is one of his most charming characteristics. Those who are privileged to know him intimately say that never have they met so noble a character. No stranger seeing him the other day, as he painfully made his way through the Jewish quarter of the East End, would have imagined that this quiet little person was “the King of Esperanto-land,” come to look upon the burdens of his brethren.

Dr. Zamenhof favoured the Jewish Chronicle with a special interview, prior to his departure from England for Nauheim, where he has gone to take the cure for a trouble of the heart, which is a source of much anxiety to his friends. During his stay in London, after leaving Cambridge, he and Mrs. Zamenhof were guests of Felix Moscheles, and I found him, writes our representative, in Mr. Moscheles’ studio sitting for his portrait. A number of telegrams had just arrived from Dover and Calais, where people were anxious to learn about his movements, as the Mayor and the Corporation of the former city were to receive him in state on his departure for the Continent, and Calais was to honour him with a municipal banquet. “You can have no idea,” he observed, “how painful all this is to me, and how gladly I would escape it all. I wish I could travel incog.”

“But you must have been gratified,” I remarked, “at the wonderful reception you had the other evening at the Guidhall from the Corporation of the greatest city in the world?”

“It was very gratifying of course,” he replied: and then he added sadly, “but it has come too late. If Esperanto could have received such recognition twenty years ago, when I was a young man and full of energy, it would have inspired me to enormous efforts, which are impossible now my health is broken.” It was a pathetic admission from a man who is only forty-eight years of age, but who looks and feels twenty years older; upon whom the fierce struggle of a chequered career have left their indelible mark of premature agedness. Dr. Zamenhof told me

The Story of his Life,

the main features of which are probably familiar to many readers; how he was born in Bielostok on the third day of Chanukah, 1859, his father and grandfather before him having been teachers of languages; the former an officially-recognised Professor of German at Warsaw, and the latter the pioneer of modern culture among the Jews of Bielostok: how having been educated at Warsaw, he went to Moscow to pursue his medical studies, and finally settled down in his present profession as an oculist, having had to undergo terrible hardships in his pursuit of a livelihood. The difficulties with which he had to contend were two-fold. He encountered prejudice as a Jew and as an idealist. As a Jewish doctor he had to confine his practice to his coreligionists, the majority of them poor, and his prospects where not improved by concerning himself with schemes which the majority of people regarded as Utopian. Even his hopes as a suitor for the hand of his present wife were jeopardised—it was the story of Akiba’s marriage romance repeating itself in modern life. Such a man, said the lady’s wealthy father, will never be able to earn a living for my daughter, and he forbade the engagement. But the young couple were determined, and their way in the end, and Dr. Zamenhof’s father-in-law became one of his staunchest supporters. Three children were born of this marriage. The two elder children—a son of nineteen and a daughter of seventeen—are pursuing their medical studies in Lausanne, the Russian universities being closed to them as Jews; but there is some hope now of their entering the University at Charkoff. Several of Dr. Zamenhof’s brothers distinguished themselves as military doctors in the Russo-Japanese War.

“You have no doubt often heard,” said Dr. Zamenhof to me, “how the town in which I was born was a babel of languages, and how its daily life was poisoned by the bickerings and animosities that arose out of this diversity of tongues. This it was that led me, as a mere youth, to dream about the discovery of some universal medium of communication that would help forward a better state of things. As a student at the University, although I was intended for the medical profession, I had devoted considerable attention to languages—Latin, Greek, French, German, English and Hebrew—an aptitude for which I had no doubt inherited from my father and grandfather. But the idea of Esperanto did not dawn on

[end left column]

me at once. It grew out of several fruitless attempts which, one after another, I discarded.”

Hebrew and Yiddish.

Did you not at one time think of making Hebrew or Yiddish your universal language?

“No, that has been stated, but I have been misunderstood. I did certainly, at one time, hope to revive Hebrew as a spoken language among my coreligionists, but I soon became convinced that that was impossible. Then, for three years, I worked with Yiddish, in the hope of placing it on a level with the cultivated languages of Europe, and I compiled a grammar of the so-called ‘Jargon’—the first Yiddish Grammar, I believe, that ever was written. But after completing it, I came to the conclusion that there is no real future for Yiddish, and so my Grammar still remains in manuscript. The conviction gained on me that, as a Russian Jew, I could only whole-heartedly give myself to devising a language which, on the one side, would not be the exclusive national possession of any single people, and peoples. Only a neutral tongue could become a universal medium of communication, and neutrality was the character which I gave to Esperanto. Esperanto belongs to the whole world, because it is derived from no one language in particular; and it is in the fullest sense international, because it has never been the speech of any on nation. Those who speak it and use it are the citizens of an ideal democracy, which we may call Esperanto-land.

“I may tell you that primarily it was in the interests of my coreligionists that I invented this language. I saw them cut off from the rest of the world by a language which they spoke only among themselves, and then in an uncouth form. I saw them shut up in a Ghetto, and thus exposed to the terrible curse of national animosities, and the walls of this Ghetto were largely constructed out of a dialect. This dialect not only served to alienate them from the Gentile world, but even from their own coreligionists in other countries who speak the language of those countries and do not understand Yiddish. Thus the Jew is separated from his fellow-Jew as well as from his Christian neighbour. I saw all this, and it determined the course of my labours. Had I not been a Jew, the idea of a future cosmopolitanism would not have exercised such a fascination over me, and never should I have laboured so strenuously and disinterestedly for the realisation of my ideal. But I was always a devoted son of my unfortunate Jewish people, and whenever my task seemed hopeless I had only to think of my coreligionists, speechless and therefore without hope of culture, scattered over the world, and hence unable to understand one another, who must needs take their culture form strange and hostile sources—and the thought of all that filled me with renewed energy. Yes, I am convinced that there is no people in the world to whom a world-wide medium of communication like Esperanto might prove so useful as the Jewish people. It would bridge the gap which in all Jewish communities nowadays yawns between the native and the foreigner, the rich and the poor, the cultured and the uncultured. This is why every time I see

A Poor Jew

who has no knowledge of a civilised language, and who, after three or four weeks, has learned Esperanto so thoroughly that he can correspond with the whole world with it, speak his thoughts freely, and this thanks to this language, feel himself a man among men—that gives me more pleasure than all the praises of hundreds of learned people. A poor Jewish shop-keeper, whose beautiful Esperantist poems are read with pleasure by Esperantists of all countries and nationalities, affords me more satisfaction than the various scientific publications of which the language already boasts so many.”

Then Jews ought to be among your most enthusiastic disciples. Have they taken up with the study of the language in any considerable numbers?

“I am afraid I must confess they have not. Still, I must make some exceptions. One of the principal Esperantists was a Jew—the late Dr. Emile Javal, of Paris, the eminent blind medical scientist, who died at the commencement of this year. He acted in former years as the Secretary of the Central Bureau, and I referred to his labours for our cause in the recent Congress speech at Cambridge. Another coreligionists, happily still active in the cause, is M. Gaston Moch, of military fame, the well-known author of ‘Sedan,’ and the brother of the celebrated deceased French military officer, Jules Moch.”

In England has it been taken up by any known persons?

“Yes, there is the Rev. Isidore Harris, who has done much by his writings in Jewish and non-Jewish, English and American, publications to popularise the study. Mr. Charles B. Mabon, Of Glasgow, has composed music for my Esperantist song, ‘La Gaja Migranto,’ which he has likewise rendered into English. And he has translated ‘Adon Olam’ into Esperanto. When I visited the House of Commons the other day, Mr. Herbert Samuel, the Under-Secretary of State for the Home Office, who received me on behalf of his Chief, told me that his wife was a student of the language, and I have no doubt that there are many private Jews and Jewesses studying the language who are not known to me. In the Address-Book (Adresaro) of registered Esperantists one can, of course, pick out a certain number of Jewish names. But not all Esperantists register themselves. I should say there are 300 or more Jewish Esperantists.”

Progress of Esperanto.

“As you are probably aware, it is just twenty years, last July, since Esperanto became public property. In 1878 I had succeeded in building up a neutral language on the basis of the Romance-Teutonic roots of modern Europe. But for five or six years I kept the idea to myself, fearing that, as a Jew, I might incur scoffing and persecution by a premature publication of so bold a scheme. It was not, therefore, until 1887 that, after several unsuccessful attempts to find a publisher, I gave forth my first brochure entitled ‘An International Language.’ It was signed ‘Doktoro Esperanto,’ that is ‘Doctor Hopeful,’ and so the language came to be known as Esperanto. Of course, I was very much perplexed in my mind before I finally decided to take the plunge. I felt that I stood before the Rubicon. Once having published, retreat would be impossible, and I knew what kind of fate attends a doctor who is dependent upon the public, if that public comes to regard him as a visionary, or a man who busies himself with side-issues. I felt it was staking my whole future peace of mind, my livelihood, and that of my family, but I could not abandon the idea which had entered into my mind and blood, and—I crossed the Rubicon.”

And you have never had occasion to regret the step?

“No; for though we had to encounter numerous difficulties in the early days, our progress has been uninterrupted and almost phenomenal. The year after my first pamphlet was published, the Volapuk Society, at Nuremberg, ceased to exist, but the majority of its members went to form the first Esperanto Club. That stood alone for three years until, in 1891, another arose in the city of Upsala, in Sweden. St. Petersburg followed suit, with branches at Odessa, and even at so distant a place as Khabarovsk, on the Amur. France and Denmark joined the movement in 1879, and Brussels and Stockholm in the next year. The first Esperantist group in Paris originated in 1900, and the next year additional groups were form-

[end page 16]

ing in Bulgaria at Brünn, at Vladivostok, and at Montreal. That was the first official appearance of Esperanto on American soil. Since then societies for its study have been formed in all parts of the world, and there are now many hundreds of them. At our Cambridge Congress we had delegates from all countries, including such remote lands as Venezuela, Tunis, Sweden, Norway, Siberia, Iceland. That Esperanto has taken such deep roots in France we owe mainly to the self-sacrificing efforts of the Marquis de Beaufort, who for many years had been at work on the invention of a universal language; but when he heard of Esperanto he generously set aside his own invention to take up with mine. Esperanto is now taught in several of the lycées and colleges, and the French Minister of war encourages its study in the army. The Belgian Government sent its official representative to the third Congress. In Russia, there are more people able to speak Esperanto than English. In England there are now sixty groups at work. It is taught in many English and Scottish schools, and had been taken up by the London Chamber of Commerce and the National Union of Teachers. There is, as you know, a large Esperantist literature growing up. The grammar has been translated into more than twenty languages and dialects, and there are at least twenty monthly journals devoted to its propaganda, including a magazine for the blind. One of the most pathetic sights at Cambridge was the group of twenty-two ‘blinduloj,’ who came to the Congress from various countries in Europe and America under the care of Professor Cart. All sort of Esperantist societies were represented at the last Congress—the Roman Catholics, the Socialists, the Peace Party, the British Medicals, the French Medicals, the Sailors, the Freethinkers, and so forth. Most of these groups have their special Esperantist organs, and the various scientific groups are beginning to issue their special dictionaries in their several departments.”

You have not a Jewish group or a magazine for Jewish Esperantists?

“No; though, as I have already said, no body of men stands so much in need of an international medium of communication as the Jewish people. A magazine published in the interests of Jewish Esperantists all over the world would undoubtedly increase the number of Jewish adherents, and might ultimately have a big success. Of course it would chiefly depend for its success upon its circulation in Russia, and therefore care would have to be taken that nothing appeared in it to which the official censor could take exception.”

I understand there is a project for rendering the Bible into Esperanto?

“A Committee is at work on this question, and it will no doubt be done by degrees. I myself have already translated Ecclesiastes, and I have promised the North American Review to undertake Proverbs. When that is finished, I shall set to work on the Psalms. Ruth was translated many years ago by Kofman. And in the New Testament, the Gospel of St. Matthew has been published in Esperanto. My work is done direct from the Hebrew, with the aid of recognised versions.”

Zamenhof as a Zionist.

I understand that you were at one time a pronounced Zionist, but now hold different views?

“I was always deeply interested in the social life of my people, and in my youth I was an enthusiastic political Zionist. That was long before Herzl came upon the scene, and before the idea of a Jewish State became popular among Jews. People mocked at me when I declared that we ought to have a land of our own. Already, in the year 1881, when I was studying at the University of Moscow, I convened a meeting of fifteen of my fellow-students, and unfolded to them a plan which I had conceived of would be the commencement, and become the centre, of an independent Jewish State. I succeeded in impressing my views on my colleagues, and we formed what I believe was the first politico-Jewish organisation in Russia. A few months later my father’s financial position obliged me to leave Moscow and return to Warsaw. There, also, I commenced an active subject in the Russo-Jewish journal, Razsvjet, entitled ‘What We Ought to Do.’ In that article, signed ‘Hamsefow,’ I explained in detail that the eternal sufferings of our people would only come to an end when they became the majority of the population in the places they inhabit; for the strong are always in the right, and the weak are always in the wrong. So I recommended that the Jews should choose some very sparsely-inhabited spot in the United States of America, and colonise it in such numbers that sooner or later they could form it into a Jewish State, in the same way as the Mormons have done in Utah. My article, which was written shortly after the first anti-Semitic outbreaks, created a sufficiently deep impression. But about the same time, the Jewish journals, Hamagid and Hashachar, started a propaganda for the colonisation of Palestine. Realising that before all things we needed unity if our efforts were to succeed, I published a further article in the Razsvjet, recommending that we should not split up into different sections, and, therefore, although America was much better suited for our purpose than Palestine, we should concentrate our labours on Palestine.

“So I founded among the Jewish youth of Warsaw the first society of ‘Friends of Zion.’ I drew up the rules, hektographed them myself, and distributed them, arranged meetings, concerts and balls, enlisted recruits, and established a patriotic Jewish library. Branches of our central organisation sprang up the various cities of Poland and Western Russian, and from all of these organisations I collected monthly subscriptions for the colonisation of Palestine, which I transmitted to Rabbi Salvendi, in Nuremburg. And when our society of young people was sufficiently strong, we extended our operations to older people, and suggested that they should establish a larger society at Warsaw of ‘Friends of Zion.’ Such a society was founded, with advocate Jasinowski as President, the publicist, Rabinowicz (Schefer), as Secretary, while I was at the head of the Executive. About that time I finished my University course, and set up in practice in quite a small village. The tranquil life of the place in which I now lived was conducive to thought, and brought about a complete change of my ideas. Gradually I came to the conviction that Zionism was a beautiful and impractical dream; that it would never solve the eternal Jewish question. The solution must be sought along other lines. You may imagine that is was with no little grief that I decided to abandon my Nationalist labours. But thenceforth I was to devote myself to realising that non-national, neutral idea which had occupied my mind of my earliest youth—to the idea of an international language.”

Hillelism and Esperantism.

“From the year 1884 to 1901 I stood quite aside from the Jewish national movement, and I did nothing for the Jewish question. But though I did nothing, I thought much, and I was constantly searching in my mind for a solution to the Jewish question. Finally, at the commencement of 1901, I decided to send forth the fruits of my seventeen-years’ cogitations. I published in the Russian language, under the pseudonym of ‘Homo Sum,’ a fair-sized pamphlet, which I entitled: ‘Hillelism, a project for solving the Jewish Question.’ I analysed the essential features of Judaism, I detailed the history of the Jews, the causes of their two-thousand years’ wanderings, the ideals of ‘Zionism’ and ‘Assimilation,’ and upon the basis of these facts I endeavoured to show how the

[end left column]

Jewish question could be most effectually solved. These were the conclusions I came to:—

“The historical fact that other people and human groups have only suffered for a short time, and afterwards they either recovered their position or perished, while we have suffered for 2,000 years, and are unable to find for ourselves anywhere in the world a tranquil corner—this shows that the cause of our sufferings is not external, but internal. The cause of our endless golus is this, that everywhere Judaism still preserves its national character, while, as a matter of fact, the Jewish nation as such ceased to exist 2,000 years ago, and Judaism, rightly understood, is an idea—a creed. The pseudo-national-Palestinian character which our religion has come to assume has resulted in this: that everywhere and always we regard ourselves as foreigners, and therefore we are without a home and soil. Consequently, in order to solve the Jewish question, we need to reform our religion, but not to abandon it. Judaism as a religious idea must be eternal. Never can we Jews be satisfied to remain without a religion—‘confessionslos,’ as they express in Germany—nor can we accept any other religion as a substitute for our own. How are we to reform it? By giving up its pseudo-local character, and by giving it a character such that we can hold it without untruth, shame or hypocrisy. In order to do this, we should give our religion the character of Hillelism. By this, of course, I mean that we should accept as its fundamental basis only the idea of philosophically-pure Monotheism, and the somewhat modified principle of Hillel that the one law of our religion is the love of our neighbour. All other Jewish institutions are not laws, but customs and traditions. They are worth preserving, but are not obligatory. A Synod should be appointed to improve and develop them. When we profess such a religion, then we shall be strong, for then we shall be able to tell our children that we are doing battle for a holy and noble idea.

“But when I speak of reforming our religion, I do not mean that we should proceed on the lines of those Reform parties who make changes only in order to mask their Judaism and assimilate themselves to the Gentiles, who do not want them and would rather be without them. That is not my idea of a real Jewish Reform. Inasmuch as all Jews have a history in common, and the peoples will have nothing to do with us, we ought to beware of calling ourselves ‘Russians,’ ‘Germans,’ etc., and we should call ourselves ‘Jews’ by nationality; always remembering that, unlike other nationalities, ours is neither local nor ethnological, but only ideal.”

A Normal Sect.

“It stands to reason that we cannot reform the whole Jewish people at one step. So we ought to create in Judaism a normal sect, and strive to bring it about that that sect may come, in course of time—say, after 100 or 150 years—to include the whole Jewish people. We should then become a powerful group. Nay, more, we should be in a position to conquer the civilised world with our ideas, as the Christians have hitherto succeeded in doing, though they only commenced by being a small Jewish body. Instead of being absorbed by the Christian world, we shall absorb them; for that is our mission, to spread among humanity the truth of Monotheism and the principles of justice and fraternity. That was what the Hebrew prophets aimed at. And because we have not set about doing this, therefore we have suffered; and until we do attempt it, and cease to be the abnormal people that we are, we shall continue to suffer. That was what Moses foretold in the Tochacha and in Ha-azinu.

“Therefore I proposed that those who approved of my idea in principle should call together a Jewish Congress, and found a sect of Jews professing clearly-defined fundamental principles. They should establish a philosophically-pure creed, and preserve the various Jewish customs and ceremonials, feasts and fasts; not, however, as laws, but as traditions—as beautiful symbols of eternal truths. And in order to carry out their idea they must have an ideal language; an easy means of inter-communication—not Hebrew, which is too difficult for this purpose, and has never been acquired, or can be acquired, by the majority of Jews—a language which they can also use in their prayers; so that they will not need to use the language of peoples who are strange and hostile to them. Besides a local centre, where their Synod should reside, and where they can concentrate and grow strong. I see no reason why this centre should not be placed in our natural Fatherland, so that the ancient Prophetic ideal might be realised: ‘For from Zion the Law shall go forth, and the word for the Lord from Jerusalem.’”

Did you succeed in making many converts to your ideas?

“No, the Russian Jews would have nothing to say to it. Many persons confessed to me that in their hearts they agreed with me, but they had not the courage to help me in organising such a sect as I contemplated. There is a Russian proverb that [says] ‘One man in a camp does not make a soldier.’ So I have long since abandoned my scheme as unworkable, and my efforts are now devoted to the cognate object of furthering the movement which I have called Esperantism. What I mean by Esperantism I explained in my Congress speech. Its ideals—apart from the utilitarian purpose of the Esperanto language—are purely humanitarian. We wish to create a common ground on which the various races of mankind can peacefully and fraternally mingle, not intruding racial differences in any way. The

[end page 17]

ideal is simply expressed in these few lines, which your readers will probably be able to understand, though they may not be Esperantists:—

Sur neutrala lingva fundamento,

Komprenante unu la alian,

La popoloj faros en konsento

Unu

grandan rondon familian.

In the Russian Ghetto.

As Dr. Zamenhof lives and works in the heart of the Russian Ghetto, I interrogated him as to the condition of affairs at the present time.

“There have been no pogroms in Warsaw,” he replied, “because there the Jews and the Poles make common cause, and are strong enough to repel any attack. All the same, things are terrible, and the emigration from Warsaw is, in consequence, colossal. Many hundreds of emigrants pass through my hands in the course of a year. They come to me in whole families to be examined and treated for trachoma, the appearance of which would prevent their admission to America and other countries. Yes, I think that ultimately affairs are bound to improve in Russia, because once the people have been given a taste of freedom, they will never be satisfied till they get it.”

Dr. Zamenhof expressed a desire to see the immigrants from his native country in their English surroundings, so we made a tour together of the Jewish quarter in Whitechapel, and paid a visit to the Leman Street Shelter, where the founder of Esperanto was officially received by Mr. Hermann Landau. It was touching to see these two men meeting for the first time, both engaged in the same kind of work, and eagerly comparing notes on their common experiences. The arrangements made at the Shelter for the reception of refugees naturally interested him greatly. As we looked out of one of the windows into the Tenter Ground, where crowds of Jewish children were noisily romping, Dr. Zamenhof remarked: “How different from Russia, where the children are prematurely anxious, and are almost afraid to play in the streets!”

NOTES:

עניו = ONEV = meek/modest person (Yiddish), humility (Hebrew).

‘neutrala’ in Esperanto correctly should read ‘neŭtrala’.

‘Marquis de Beaufort’ should read ‘Marquis de Beaufront’ = Louis de Beaufront, a foremost advocate of Esperanto in France at that time, who would later perfidiously support the break-off rival artificial language Ido.

‘Hamsefow’ = Zamenhof pseudonym?

[says]: There is a blank white space in the original where this word presumably belongs.

‘Airurgiistoj’ (see below) is probably a typo for ‘ĥirurgiistoj’ = ‘surgeons’.

The large advert in the bottom right hand corner of page 17 reads (English translation in the right column):

|

“Nutraĵo sen egalo” Dro. Andrew

Wilson, LA KAKAO 300 “Neniam mi gustumis kakaon tian, kian mi tiel Sir CHAS. CAMERON, C.B., M.D., Eks-Prezidanto |

“Nourishment without equal” Dr.

Andrew Wilson, The Cocoa bean 300 “Never have I tasted cocoa which I Sir CHAS. CAMERON, C.B., M.D., Ex-President |