The development of a radical critique of science and technology should have much to gain from students of the history, philosophy and social relations of science. However, most work in these academic fields reproduces — rather than critically analyses—the existing approaches to understanding the nature of scientific thought and practice. The history of science is dominated by studies which take no account of social and political influences on scientific ideas. The philosophy of science is preoccupied with formal systems and logical issues; the sociology of science with models drawn from the very sciences upon which it is supposed to be shedding new light. Studies in the social relations of science—both current and past—characteristically employ a narrative rather than analytical historical style and a use/abuse model of evaluation. The result is that the academic study of science is almost wholly lacking in a radical, critical dimension.

Marxist studies might be expected to illuminate these questions. However, the attention of marxist scholars has been largely devoted to the historical and human (or social) sciences. Marxist studies in the natural sciences are relatively undeveloped. Entering the literatures of existing approaches is far from easy, and their main examples are seldom tied to particular historical case-studies.

Various marxist tendencies have gone some way to developing critiques of the natural sciences. Lenin, Trotsky and Mao, following Marx, have looked at science's roots in the productive process and tried to analyse the relationship between science and technology and their (future) place in a socialist society. All three were faced with these issues as practical problems: Lenin as a leading and founder member of the Russian Bolshevik Party; Trotsky as Chairman of the Scientific Technical Board of Industry in Russia in the 1920s; and Mao as Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party throughout the period of China's enormous technological advance. Other, more academic, writers leading on from (or away from?) Marx have

104

____

____

105

seen science as a superstructural reflection of the economic base of a given society (e.g. the Russian historian of science Boris Hessen); or have interpreted science in a wider totality of relations, laying greater stress on symbolic and other theoretical elements (Frankfurt School - Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse, Jürgen Habermas, Alfred Schmidt, Trent Schroyer); or have proposed a new interpretation of Engels’ ideas of objectivity which is based on a parallel between classical science and Marx’s later ‘scientific’ work, and which demarcates scientific knowledge sharply from ideology (the French School centred round Louis Althusser).

Within the bourgeois academic tradition there are three bodies of literature which have attempted to draw on the insight that science and society must be seen as importantly related, but without wishing to draw conclusions which would undermine the basic structures of the existing social and political order. Work in the ‘sociology of knowledge’, which began with Karl Mannheim’s softening of views of Max Weber and Georg Lukács, is coming into greater vogue as a result of the alliance which Berger and Luckmann have forged with phenomenology. Academic functionalist ‘sociology of science’ has developed primarily in America in the wake of Robert Merton’s application of models drawn from biology to the study of science as part of a stable society (organism). There have been significant cross-currents of ideas between the sociology of knowledge, sociology and anthropology. In anthropology itself, an approach has recently emerged under the loose heading of the ‘anthropology of knowledge’ in which Mary Douglas and Robin Horton have suggested that science should be looked at as a belief system of a particular cosmology, just as other societies’ belief systems are examined and interpreted.

All of these individuals and groups have something to say on the relationship between science, technology and society, and a radical critique of the relationships will involve an understanding of their positions. We hope in future issues to provide annotated reading lists on these approaches to science, its history and its social, political and ideological relations, including critical commentaries. This is itself a formidable task, even if the aims are limited to critical exposition.

That the rise of modem science is connected with the rise of capitalism is a thesis that every marxist would wish to support. But the relationship between the content of scientific ideas and socio-economic variables is the one which is least clear. The relationship between the rise of capitalism and the rise of science as an activity and as a world view is vexed enough. It was the subject of a heated debate in the historical periodical Past & Present from 1964 onwards, and historians remain vague about it. For example, the marxist historian E.P. Thompson wrote in 1965, ‘The exact nature of the relationship between the bourgeois and the scientific revolutions in England is undecided. But they were clearly a good deal more than just good friends’ (Socialist Register, 1965, p. 334). A decade later, no one

___

106

seems at all certain about any of the three main levels of the issue: the socioeconomic relations of science as an activity, as a world view and as a growing body of theories and findings. These are problems for historians and for scientists and technologists.

The consequent questions are many and important. How is ‘modern’ science to be distinguished from ‘non-modern’ science, scientific enquiry from other forms of enquiry? What are the relations between science and ideology? Are they sharply distinct? Is science progressively eliminating the domain of ideology? Or is science an expression of ideology? Is there a special form of revolutionary activity for scientists and technologists? Some would argue that science has legitimate claims to objectivity but that it has an ideological role and set of relations as well: that the two aspects are inseparable, just as fact and value are.

Another important and vexed set of questions involves the appropriateness of the concepts of ‘base’ and ‘superstructure’ to the analysis of science. Is science a productive force and therefore part of the economic ‘base’ or does it (also?) in some way reflect the economic base and belong to the ideological 'superstructure'? Will socialist scientific knowledge differ qualitatively from capitalist scientific knowledge? Hitherto, science has been carried on as the work of a ‘scientific mind’ divided from the workers’ bodies. What will happen to the scientific head when, as a result of a socialist revolution, the workers’ control of production places that head on their own shoulders? Will they be able to do so, and will the head remain the same or will it change as a result? What will science be like when it is carried on as the productive force of the producers, compared with science acting at present as a productive force in the service of capitalist power over the producers?

Looking at these same issues conceptually, is the base-superstructure model, however complexly elaborated in terms of ‘mediations’ and interactions between base and superstructure, an acceptable theoretical framework for an understanding of modern science and its development? If not, can the model be sufficiently enriched, or must it be totally replaced by some conception of a totality of relationships or something which has not yet occurred to socialists living in a context which so actively discourages seeing the structures which will shape a human world? The most restrictive view of the relationship of science to the wider society is a narrowly determinist one in which all ideas— including scientific ones—are mere ideological reflexes of economic and technical constraints and requirements. If we oppose this with a more comprehensive framework, what degree of autonomy has the superstructure—including scientific thought—from the base? The work of Alfred Sohn-Rethel cannot be readily assigned to any one of the groupings outlined above. Perhaps it could be argued that his early development in Germany was closest to the Frankfurt School, but his academic career was long-delayed by Nazism, since he had to flee to

____

107

Britain when his underground work was discovered before the Second World War. He continued to develop his ideas on the relations between mental and manual labour from a marxist perspective, while earning his living as a school teacher. In 1970 he published a book in this area which was immediately pirated by interested student readers who objected to the price of the official edition. He has since been appointed to a professorship at Bremen. George Thomson’s comments on his book give some idea of its scope:

When studying the economic basis of tragedy . . . I realised that my conclusions must apply equally to other ideological products of ancient democracy. Accordingly, in the present volume, I have examined the part played by commodity production and the circulation of money in the growth of Greek philosophy. In this I am greatly indebted to Dr Alfred Sohn-Rethel, whose study of Kant has led him independendy to similar conclusions, to be published in his Intellectual and Manual Labour. Not only has he permitted me to read his book in manuscript, but in discussing my own he has helped me to appreciate the profound philosophical importance of the opening chapters of Capital (The First Philosophers, 2nd edn., 1961, p. 7).

Sohn-Rethel was thus extending his analysis from traditional domains of study of relations between the economic and the cultural to include new domains. In a later study he touched on scientific management and on science itself ‘Mental and Manual Labour in Marxism’ (in Walton & Hall, eds., Situating Marx, 1972). He was invited to focus on science in a seminar he gave that same year to the Wellcome Unit for the History of Medicine at Cambridge, and he developed it further in a talk given in the series on ‘Alienation’ at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1974. The present paper is drawn from that talk, which the RSJ collective asked him to make available in a publishable form. Members of the collective were very interested in the article but had two sorts of reservations. The first was that its language was difficult for two reasons: first, because the author’s native language is German, causing problems of expression which do not arise in conversation; second, because his long familiarity with marxist debates makes inevitable the use of terms which may be unfamiliar to many of our readers. With Sohn-Rethel’s permission, members of the collective completely rewrote the article, adding annotations, definitions and further reading. The draft was then sent to him, and his extensive comments, alterations and additional passages have been incorporated into the text. The second reason for our reservations lay in the relationship between his analysis and existing marxist debates on science. We are therefore publishing the article as a first step in a debate which we hope will be catalysed by his strong claims, and we are grateful to him for allowing us to draw him out beyond his own surer ground in order to make a contribution to that debate.

Our own conceptual reservations are of two sorts. At crucial points

___

108

in the argument, he suggests that a longer account could be given which traces the relations between economic structures and scientific laws. That is, having pointed out what we consider to be important formal analogies, homologies and parallelisms between commodity formations and scientific conceptions, he implies that a detailed genetic, causal account could also be given. We feel that the demonstration of formal congruences would itself be a significant contribution but that, at the present stage of the debate, the relationship between this and precise explanations of the socio-economic causes of a given scientific theory are problematic. Put crudely, we do not yet know where we are between an account which says, ‘It was no coincidence that this happened in science while that was happening in capitalism’ (Darwin’s natural selection theory was developed in the high period of competitive capitalism, for example), and one which says, ‘The development of hydraulics was determined by the needs of the mining industry.’ The first is illuminating but too broad, while the second is both implausible in this simple form and too narrow. We think it prudent of the author to have refrained from giving detailed causal accounts; we are not at all sure that they will have a significant place in a marxist analysis. The point of analysis is to provide a basis for further practice in the field concerned. Thus one has to be able to identify the major determinants of a situation so as to be able to intervene effectively.

Our second conceptual reservation comes from the internal history of the change from Aristotelian to Newtonian physics. Sohn-Rethel claims that the Galilean concept of inertial motion is the distinguishing conceptual feature of modern science. He argues that this concept evolved as a consequence of the nature of the capitalist mode of production, and argues further that Galilean science has produced objectively valid knowledge of nature that can, however, be correctly understood only in a socialist society. But look carefully at the intellectual history: Galileo, as both a committed Copernican and committed believer in the mechanical philosophy, was compelled by the logic of his position to claim that the earth’s circular motion around the sun is natural, i.e. inertial. For to have upheld the Aristotelian belief that the natural place of earthly matter is to be at rest in the centre of the cosmos would have left the Copernican Galileo with the impossible task of accounting for the fact (as he maintained) that the planet earth annually orbits the sun yet with no forces acting on the earth. For Galileo, the mechanical philosopher, could not and did not believe in the existence of occult forces, i.e. forces acting at a distance through the power of ‘sympathy’ or ‘antipathy’. He roundly rebuked Kepler for maintaining such beliefs. Thus, for Galileo, the earth’s circular motion had to be inertial: there seemed no other rational choice. (Descartes, however, was to provide an alternative explanation in terms of vortex motion.) Given this situation in the internal logic of Galileo’s position, it could be argued that the internal aspect of this episode in the history of ideas about Galileo’s reasons

____

109

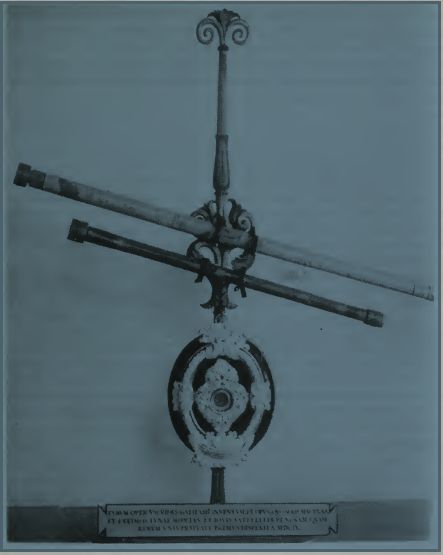

Galilean telescopes

___

110

for introducing his concept of inertial motion does not call for an account such as Sohn-Rethel’s. In that sense, the internalist would consider his analysis ‘unnecessary’. The RSJ collective would go on to say, however, that an account which appears not to call for further explanatory factors may demand them for marxist reasons, as a condition of replacing a bourgeois academic level of understanding by a political level.

In his comments on our draft of this editorial introduction, Sohn-Rethel takes strong exception to the argument that the internalist account could even appear to be complete. He writes,

Galileo’s notion of inertial movement (or Descartes’ first explicit statement of it) was not gleaned from nature, not even from astronomy, Copemican or Keplerian, as the movement of the celestial bodies is not rectilinear. In fact, inertial movement is not an object of observation, as Koyré argues forcefully. Thus without “Sohn-Rethel’s analysis” the Galilean concept of inertia and Newton’s “first law of motion” remain totally inexplicable as to their source and legitimacy. Galileo’s inertial motion was in a straight line, conforming with the axioms of Euclidean geometry. It cannot, therefore, be empirically related to, or theoretically derived from, the circular or elliptical inertia of the classical bodies as interpreted by Copernicus or by Kepler. The genetical and logical source of the concept of inertia at the root of classical mechanics still demands an explanation, and I cannot agree that my analysis is or could appear to be unnecessary. Ernst Cassirer’s study of “Einstein’s Theory of Relativity” (Substance and Function and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, Dover) contains a cogent argumentation to the effect that the advance from Newton’s to Einstein’s theory could not have proceeded if the Galilean inertia were based on any kind of physical reality. It is precisely the lack of such reality to which it owes its fundamental methodological importance as the key concept of classical mathematical physics. But even though Cassirer is correct in the way he poses the epistemological question regarding the Galilean concept of inertia, he has no satisfactory answer to it.…

as Sohn-Rethel claims to have.

It is obvious from this sharp disagreement on the history of ideas within physics that a more complex discussion is required than the one presented in the following article, if only because our remarks elicited this important futher analysis of the issues as seen from inside the natural philosophy of the period. However, we would like to stress that issues at another level cry out unmistakably for marxist analysis. How are we to explain (1) the commitment to and articulation of the Copemican world system and the several mechanical cosmologies of the time and (2) the subversion of those mechanical philosophies by the rise of a cosmology in which the finite cosmos would become an infinite universe? This much more sweeping change made rectilinear inertial motion reasonable, whereas it had been ‘inherently absurd’ in a finite cosmos. The concomitant introduction and acceptability of the existence of ‘occult forces’ acting at a distance, i.e.

____

111

gravity, was necessary if inertial motion could no longer be thought of as circular. Such an analysis would, we feel, not only entail consideration of the rise of commodity production — and the ‘technical needs’ of the emerging bourgeoisie — but also the explicitly stated goal of the ‘domination of Nature’, the importance of the Hermetic and associated traditions in the Renaissance, the impact of the Reformation, and—last but not least—a consideration of the ‘internal logic’ of the Copernican/Newtonian revolution.

Other ways of approaching aspects of these crucial developments in the formation of the modern scientific attitude also call for ideological and historical analysis. Surely ‘it was no coincidence’ that a political theory of possessive individualism, with laws defended as a way of avoiding random collisions of individual pursuers of pleasure and avoiders of pain, developed

in a period of interacting atoms guided by mathematical laws in science. Surely it is worth looking at the relationship between the doctrine of primary and secondary qualities in science, closely allied with the banishment of purposive explanations, and the hegemony of commodity relations in the development of capitalism. Similar parallels in the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries cry out for analysis of formal congruences of the basic structures of the economic and intellectual formations. Sohn-Rethel has launched what we see as a new, critical attempt to bring such relationships into the domain of marxist analyses of science. Now we must conduct those analyses.

Returning to a point raised above, what about science in a socialist society? What, if anything, would change? In a successful, thorough socialist revolution it is obvious that the mode and social relations of production would change. The priorities of resource allocation would be changed. The hierarchical and elitist and racist and sexist and ageist character of capitalist science would be changed. But the theoretical and technical achievements of existing science would not disappear. Newton’s laws and ‘Schroedinger’s equation’ are theories which correctly describe the behaviour of matter in limited domains of applicability and to a certain degree of accuracy. What would, however, certainly undergo change in a life-enhancing society is the overall world view—the cosmology in which Newton’s laws, quantum mechanics and other scientific theories find their human interpretation. What perhaps at present appears to be the only possible way of interpreting the significance of these theories would, we feel, come to be seen as a world view that reflects and partly makes ‘natural’ an alienated, basically joyless mode of being in the world.

However, the main task for revolutionary scientists and technologists is not so much to try to construct a detailed research programme for socialist science—in any case this is not possible until they are firmly socialised in a socialist society—but to engage in activity which will lead to the building of such a society. This activity will take many forms—trade union struggle, fights for democracy in labs, etc.—but an important part of it must be a

___

112

critical analysis of the determinants and functions of science and technology in our present society. Without such an analysis, our activity may well be mindless and ineffective.

Mathematics and the natural sciences are usually considered to be independent of political and ideological determinants. Both have come to be seen as models for rational thought, and the method of science is offered as the only path to relatively objective and trustworthy knowledge. So goes the orthodox view, and indeed some of the most striking examples of the abuse of power in modern history—such as the ‘Lysenko affair’—have been concerned with attempts to suppress, delay and distort the findings and theories of science. [1] Yet a centralelement of marxist thought is that all theoretical constructions are, in the last analysis, determined by social existence and that in every epoch the ideas of the ruling class are the ruling ideas. [2] Marx characteristically applied this analysis to social and political/economic ideas, such as the category of ‘labour’. [3] Can the same type of analysis be applied to the ideas of mathematics and natural science?

I believe that the possibility of socialism presupposes the primacy of society over science and that in order to bring about the necessary reorientation of priorities, it is necessary to unmask or ‘demystify’ the a-historical, timeless and universal claims of mathematics and science. I would go further and say that the special claims of these intellectual formations play an important role in justifying, and hence maintaining, the distinction between mental and manual labour, a crucial distinction in maintaining an authoritarian and hierarchical social order. It therefore becomes an important task for marxists to demonstrate that the logic of scientific thinking originates in social history.

My strategy in this paper is to attempt to do this with arguments drawn from the period in which abstract, intellectual reasoning first appeared in our civilisation—the sixth century BC—and to apply the general position further to a scientific theory which was central to the development of modern science: Galileo’s law of inertial motion. [4] In this way I hope to attack the norm of timeless-universal logic at its inception, and in a crucial modern case. In so doing I hope to take all justification out of the beliefs in an intrinsic necessity for the separation of intellectual from manual labour.

My central thesis is that the forms of the social relations of production are the determinants of the forms of thought; in particular that there is a determinate relationship between the mode of scientific reasoning and the commodity exchange abstraction. Only by tracing this historical determination is it at all possible to understand the logic of conceptual and scientific thinking. I should stress at the outset (as I have done elsewhere) that I am not proposing simple parallels between science and the economy, much less

____

113

a one-to-one correspondence between the requirements of technology and the findings of science. [5] I am concerned with derivations requiring a much more penetrating and incisive kind of analysis than a mere search for simplistic parallels or for ‘explanations’ of science as a reflex response to this or that technique and practice of production.

Before beginning my argument, I would like to make two very important disclaimers. It is necessary to make them at an early stage because I find that sympathetic and comradely readers have made interpretations of my work which are at variance with my true theory. In particular, this is so of the members of the Radical Science Journal collective who (with my enthusiastic approval) have attempted to ‘translate’ my lecture and to make it more accessible to English-speaking readers. As a consequence of what I consider to be various misunderstandings and ‘mistranslations’ of my ideas, I have submitted alternative passages in a number of places and have trusted the RSJ collective to interpolate them into their text. This has produced, in some cases, a less clear presentation, but it is a more faithful one. My remaining disclaimers point in two directions and involve matters of deep debate in marxist critiques of science. In one sense my interpreters would wish to make much more of my theory than I would, and in another they wish to grant much less than I claim. That is, unlike some other socialist analysts of science, I do not wish to weaken the distinction between science and ideology and to interpret science as ideology. On the other hand, in their editorial headpiece to this article, the RSJ collective compliment me for pointing out what they consider to be ‘important formal analogies, homologies and parallelisms between commodity formations and scientific conception’ and (in an earlier draft of my paper) refer to ‘congruences’ between economic abstractions and scientific ones. My reaction to these compliments is to reject them, since I claim that my theory does much more, and extends beyond this level of interpretation.

I will try to illustrate the theoretical issues involved by reproducing a passage from the RSJ draft, followed by my reply. This is not a mere textual quibble: it raises fundamental issues concerning the understanding of the relationship between science and capitalism in the present, and science and socialism in the future. My ‘translators’ wrote as follows about my argument:

If the analysis succeeds—or helps others to do so—it will bring the timeless, ahistorical and ideal categories of science into the domain of ideological analysis. The mental and ideological phenomena which Marx discusses in, for example, The German Ideology, in terms of alienation, reification, fetishism, false consciousness, etc., and which he shows to be expressions of economic exploitation, private appropriation and class division, could be extended to include the categories of mathematics and natural science.

My reply to the RSJ collective shows our sharp disagreement: ‘I do not

___

114

place science and the conceptual powers of cognition on a level with ideology. Science has objective validity; it accomplishes tasks of social necessity, although it does this with a false consciousness. The traditional and academic philosophies of science are ideology, not science itself. Mathematics is not ideological, even though it is a phenomenon of consciousness. Marx draws a deep line of division between the ideological forms of consciousness and its capacity to achieve objective knowledge (which I may term its cognitive faculties). Marx never lists science among the ideologies which, in the famous Preface of 1859, he enumerates as “the legal, political, religious, aesthetic or philosophic—in short, ideological forms” (Marx & Engels, Selected Works in one vol., Lawrence & Wishart,1970, p. 182) or among “superstructural phenomena”. This division between science and ideology must not be blurred or put in doubt.’

Turning now to my second disclaimer, I wrote as follows to the RSJ collective about their editorial introduction and certain passages in their ‘translation’: ‘That which I object to more than anything else and what I regard as a definite misrepresentation of the real meaning of my theory is your expressing it in terms of “analogy, congruence, parallelism, etc.” which I am said to show to exist in “social being” on the one side and in “consciousness” on the other (to use the marxian expressions here for brevity’s sake). If we are agreed—as I think we are—that there cannot be any other expression or representation of pure form abstractions than pure concepts, then it is sufficient to prove the existence of such form abstractions to account for such concepts. There is no “gap” left between the two spheres or ranges of being and thinking, no mere analogy or similarity or parallelism. The crux of the matter lies in proving the independent existence of form abstractions prior to the existence of appropriate concepts. And this is the brunt of my theory: that it proves the existence of pure form abstraction being involved in commodity exchange, and one that is caused by human action, not by human thought, in a way hidden to the people when and where and while they cause it. This is the vital point which, therefore, must be made as cogently and compellingly as possible. Once this crucial point has been established, all that requires further explanation are the circumstances which have caused the hidden form abstractions to have struck people’s minds at one date and locality in history rather than another. But this is a matter for historical argument, no longer one of theory and epistemology. Or to put it more accurately, I claim my theory and analysis to be a true example of marxist historical materialism in that the logical and the historical strands of the argument become inseparably linked or—to call it by its technical term— “dialectical”.

‘If you find my theory mainly “important analogies” and add, “he implies also a causal account”, only to go on to say that you consider such causal attempts premature, then, please, allow me to explain to you the cardinal content of my theory. It is to say that I have penetrated the secrets

____

115

of conceptual abstraction to the point of tracing its original formation from the realm of thought, where it was hitherto regarded as specifically rooted to the social process. Now, conceptual abstraction can be likened to theworkshop of all scientific formations, ancient, modern and contemporary. By showing that it derives (!) from the social process and that there exists a real abstraction operated by human social action (e.g. commodity exchange) which can be proved to be genetically and logically prior to the ideal abstraction operated by thought, one changes epistemology to an extension of historical materialism. This is the basic thing to be needed for laying the ground upon which a ‘radical science’ and a radical critique of alienated science can be placed. This does not come at the end or in the middle of radical science, but it is the entrance to the whole undertaking. Everything else done in the name of radical science or of its critique is premature, if this foundation of the undertaking is not established in the first place. (If this principle is not clearly brought out in the text of my article, then the publication of it in your Journal misses its purpose.)

‘It is on this basis and on this basis only that you can make the structure of society the measure of the form and function of science, that you can follow through the changes in science as a historical process conditioned by definite fundamental changes in the formation of man’s social existence in Nature, i.e. that you can obtain an idea of what science amounts to for giving mankind the right or the wrong productive forces in its existential relation to Nature.

‘It is also the clue for establishing the social class issue as it applies to science, by looking at the relation of mental to manual labour. This was furthest apart at the beginning of commodity production—which only arose because social production, formerly carried on in common and in the context of what I term a “society of production”, broke up into a multiplicity of private producers working independently of one another and thus having to rely on the exchange of their increasingly specialised products as commodities—in order to give to the division of labour the social coherence required to make it possible, thereby starting the whole historical evolution of “societies of appropriation” culminating in capitalism.

‘Now, the relation of mental to manual labour also remains a closed book unless you realise that the mental labour divided from manual labour is couched in terms of the social synthesis and of the real abstraction operating in it, in other words, unless you realise that conceptual and scientific thinking is social thinking or the socialised form of the human mind which becomes indispensable when manual production loses its original social capacity. Thus the changes in the relations of head and hand depend on the changing degree of the individualisation of manual labour. This individualisation was extreme so long as production was carried out as peasant and artisan production—that is to say, until the end of the Middle Ages. Then, from the fifteenth century onwards, production assumed an increasingly

___

116

social magnitude and content, which caused its growing dependence on capital and ended up with placing it under capitalist control. While this happened in the economic field, there arose in the mental and political sphere the fusion of the previously divided spheres of the literate and the illiterate classes and between the Church/State and the dependent population, and, closely linked with this, the division of the world into the sublunary and the translunary spheres. While production was single small-scale, the social cast or providers for the social tasks had to stand outside production. But as production became social, it absorbed that separate sphere, and we witness the fusion of them—economically, politically, ideologically— into, among others, the Copernican infinite universe governed by the same laws of physics and mechanics.

‘All these changes, which you make a reason for reservations to my theory, this theory really serves to explain. Of course my theory leaves an enormous lot still to be done, but I maintain that it supplies the methodological foundation on which all this work can be done. So long as the theory of science remains the preserve of a separate epistemology, all this work must remain stunted, superficial and groping about in trivial details, without really breaking into the sanctuary of bourgeois intellectual prerogatives. Only the critical liquidation of this entire traditional epistemological reasoning, which I claim to have achieved, creates the possibility of what you are setting out to do in your Radical Science Journal and in the books which it is going to start publishing before long, providing it proceeds on a solid theoretical foundation.’

The RSJ collective and I are agreed that the above quotations from my reaction to their ‘translation’ of this article provide a clear expression of some of the issues which divide us and which are at the centre of attempts to provide a marxist account of science. The RSJ collective also feel that my strong reaction to their attempt to clarify my ideas is itself the clearest expression in English of those ideas. Now, to resume the argument with a text which they have prepared and I have altered in places.

As I argued in an earlier paper, if our faculty of mathematical reasoning— or if certain axiomatic principles of modern science—could be accounted for by conclusive formal derivation from elements of the social base of the historical epoch concerned, then idealism would have its foundations cut from under it. [6] If the social bases underwent certain deep-seated changes affecting the relation of labour to the social nexus, the forms and axiomatic principles of science would show significant changes. Indeed, such changes are apparent in twentieth-century developments of relativity theory and quantum mechanics, as compared with Galilean-Newtonian physics. Changes of this kind would also affect that actual or potential relationship between mental and manual work. Thus, a plausible case for the association of

____

117

mathematics and natural science with alienated consciousness would be a contribution toward the building of socialism through the demystification of science and by making us comprehend the real historical connection between our social relations of production and our understanding of nature.

Of course, it is not unusual to express doubts about science and scientists as the bearers of, and guides to, a bright future for mankind. My aim, however, is to go deeper than the waning confidence (and even distrust) of science and its abuses. My aim is to consider the nature of science, and to present it as cognition paired with alienation. This approach flies in the face of the traditional interpretation of the relationship between science and social values. The positivist attitude of orthodox science characteristically treats individual facts and theories as independent of the network of evaluative relationships in which they are embedded. [7] That same attitude treats science as a whole as independent of social values. Even the positivist scientist, however, would not deny the significance of the historical settings in which classical Greek philosophy and mathematics on the one hand, and the scientific revolution of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, on the other, arose. These two great bursts of intellectual activity were, he would grant, certainly fostered by their respective historical epochs. If he knew a bit about the history of ideas, he would also grant the central influence of Greek mathematical ideas on a crucial feature of the rise of modern science—Galileo Galilei’s philosophy of nature. But he would not wish to join the marxists in attaching importance to the relationship between the economic systems of these epochs and the particular form of abstract conceptual reasoning by which they are characterised.

For a marxist, the two historical periods in question are particularly important. During the first, commodity production became fully grown, as indicated by the invention and rapid spread of coinage in the seventh and sixth centuries BC. [8] In the second, of course, the rise of modern science was embedded in the rise of modem capitalism. Both of these stages of social development were of the greatest significance for the history of mankind. If it were possible to establish a direct link between the basic conceptual formations of Greek science and Galilean science on the one hand, and their respective historical epochs and distinctive modes of production on the other, then science would be seen to have a social nature, despite the denials of its positivist exponents and historians.

The objectivity of science demands its neutrality with respect to social issues, and this acceptance of social neutrality is part of the training that every scientist undergoes. Scientific truths are held to be valid regardless of the time and conditions of their genesis and their application. In his professional life the scientist blinkers himself from all of the rest of existence. But is this neutrality really intrinsic to science and conditional to its objectivity? Is it not perhaps a more profound blinkering—to the role played by the scientist and science in the interests of capital? In that case, the very

___

118

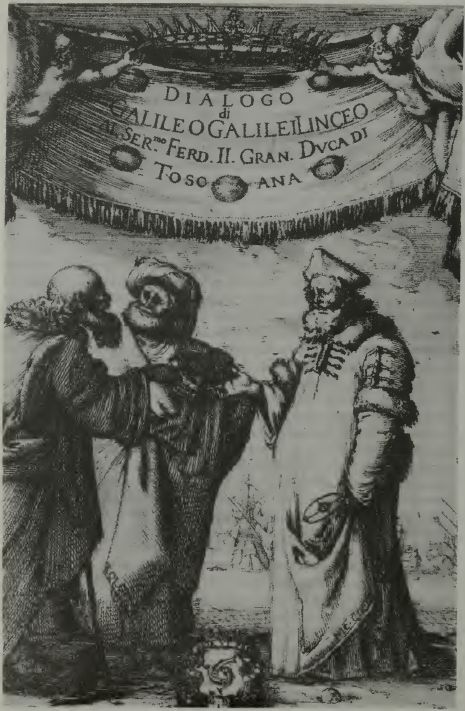

Frontispiece to Galileo’s Dialogue of 1632: Aristotle,

Ptolemy and Copernicus debate the structure of the universe.

____

119

objectivity of science would be an expression of its alienation, [9] denying the scientist a self-awareness of the significance of separating intellectual from manual labour. The critique of science as an alienated form of consciousness would require an examination of the relationship of science to manual labour throughout the stages of the development of science. Put another way, the critique of the separation of science from society parallels the critique of the separation of mental from manual labour, just as their integration is the standard by which to measure the socialist advance towards a classless society.

Whether or not science is alienated consciousness in the sense indicated can only be answered by looking closely at the historical origins of science or, more precisely, by attempting to explain science as a product of the social history of commodity production. By this I mean deriving the conceptual foundation or the logic of scientific thought from the social relations of commodity production. In other words, the aim is to do something which the positivist scientist considers absolutely impossible—a point which I want to stress. It is a common tendency of idealistic thinking—for example, in positivism and in traditional thinking (except Hegel)—to treat the logical and the historical aspects of mental forms entirely independently. [10] This tendency characterises a failure to consider the mutual and interpenetrating aspects of the terms of a relationship, i.e. it is the hallmark of undialectical thinking. [11] In positivist and traditional thought, substances and issues interact. In dialectical thought, they do not merely interact but interpenetrate, and the meanings of the respective substances or issues only exist by virtue of the relationships. Meaning is relational. The consequence of undialectical thinking in this instance is the mutual support between separating logic and history on the one hand and mental and manual labour on the other: the historical analysis carried on separately from the logical helps us to continue to consider a class society to be natural and inevitable.

Thus the issue as to whether science is essentially unhistorical, or whether it is an outcome of social history in an epoch of commodity production, is both an important and an open one. I want now to examine one particular concept, one which has played a cardinal role in the foundation of Galilean science: the concept of inertial motion. This is a non-empirical, ideal concept of motion, completely amenable to mathematical treatment, and serving as the cornerstone of the mathematical and experimental method in modern science. On the foundation of this method, science promised to be able to work out the hypothetical laws of nature in accordance with the belief that mathematics was the language of nature. Science also promised to achieve an exact knowledge of nature from sources other than manual labour—in fact, from mental resources totally alien to manual labour but compliant to the needs of capital. In the conceptual foundation of this science, all ties with historical realities are finally severed. Our task is to show the historical foundations of the concept of inertial motion and to demonstrate

____

120

that the appeal of the concept—its attractiveness as an abstract, mathematical kind of knowledge—lay in those historical foundations.

In order to be quite sure not to load the dice in favour of a marxist critique, I begin with an astute idealist witness for putting the case for inertial motion, Alexandre Koyré, who is one of the most distinguished exponents of the history of science as the internal history of ideas, thus excluding its social relations. I quote from his essay on ‘Galileo and the Scientific Revolution of the Seventeenth Century’, which is a good summary of his extensive Galilean investigations:

Modern physics, which . . . is born with and in the works of Galileo Galilei, looks upon the law of inertial motion as its basic and fundamental law . . . The principle of inertial motion is very simple. It states that a body, left to itself, remains in a state of rest or of motion as long as it is not interfered with by some external force. In other words, a body at rest will remain eternally at rest unless it is “put in motion”. And a body in motion will continue to move, and to persist in its rectilinear motion and given speed, as long as nothing prevents it from doing so.

The principle of inertial motion appears to us perfectly clear, plausible, and even “practically” self-evident . . . The Galilean concept of motion (as well as that of space) seems to us so “natural” that we even believe we have derived it from experience and observation, though, obviously, nobody has ever encountered an inertial motion for the simple reason that such a motion is utterly and absolutely impossible (given the fact that such motion would at least presuppose motion in a vacuum, through absolutely empty space). We are equally well accustomed to the mathematical approach to nature, so well that we are not aware of the boldness of Galileo’s statement that “the book of nature is written in geometrical characters”, any more than we are conscious of the paradoxical daring of his decision to treat mechanics as mathematics—that is, to substitute for the real, experienced world a world of geometry made real, and to explain the real by the impossible.

In modern science motion is considered as purely geometrical translation from one point to another. Motion, therefore, in no way affects the body which is endowed with it; to be in motion or to be at rest does not make any difference to, or produce a change in, the body in motion or at rest. The body, as such, is utterly indifferent to both. Consequently, we are unable to ascribe motion to a determined body considered in itself. A body is only in motion in its relation to some other body, which we assume to be at rest. We can, therefore, ascribe it to the one or to the other of the two bodies, ad lib. All motion is relative. Just as it does not affect the body which is endowed with it, the motion of a body in no way interferes with other movements that it may execute at the same time. Thus a body may be endowed with any number of motions, which combine to produce a result according to purely geometrical rules; and. vice versa, every given motion can be decomposed, according to the same rules, into any number of component ones. . . .

Thus, in order to appear evident, the principle of inertial motion presupposes (a) the possibility of isolating a given body from all its physical environment.

____

121

(b) the conception of space which identifies it with the homogeneous, infinite space of Euclidean geometry, and (c) a conception of movement—and of rest—which considers them as states and places on the same ontological level (meaning that rest is, as it were, only a particular modality of movement). Commonsense, indeed, is—and it always was—mediaeval and Aristotelian. [12]

Thus, according to Koyre, Galileo’s notion of inertial motion is not gleaned from experience. Consequently, it is on a totally different plane from the ideas of his predecessors, who could not tear themselves away from Aristotle and from the basic assumptions and analogies of the Aristotelian tradition which were based on artisan production first carried on by slave-labour and in the Middle Ages by serf or free labour, but in both cases considered in terms of use-value. The idea of inertial motion with which Galileo broke new ground was a non-empirical concept which offered the singular advantage of having the element of motion in common with innumerable phenomena of nature, and of being at the same time a mathematical concept which could be treated like a piece of Euclidean geometry. In fact, it opened the door through which mathematics could establish itself as an instrument of the analysis of given phenomena of movement and yield a mathematical hypothesis which could then be tested experimentally. In what follows I shall attempt to explain the concept of inertial motion from outside scientific thought, from something which is not yet science and is not even thought.

My explanation is marxist in that the forms of thought are not taken into separate consideration as a province all their own. The forms of consciousness are regarded as an integral part of social existence and as determined by the material environment and economic necessities of their epoch. The forms of scientific consciousness should not be treated as an exception to this approach. We can clear our historical field by making a broad distinction which will help us to gauge the place which science occupies in history. The distinction is between societies of production and societies of appropriation. [13] It distinguishes societies according to the functional synthesis by which they hold together and form a viable whole. I refer to this overall form of social synthesis as a society’s nexus. In societies of production the nexus is rooted in the productive activities of the people, in the communal way in which they carry on production. Whether the people work as a collective or in separate groups or singly, they know what the others are doing. They act in concert according to custom, a council of elders (who may, of course, control the power structure), or some such set of institutions found routinely in comparatively small social units. What we find on the basis of such 'communal modes of production' (as Marx calls them) is that their practice is rational, i.e. makes sense to outsiders, but their theory is irrational

____

122

(looks bizarre to others). They have a firm control over their social life process and usually regulate it to the smallest detail, but in their judgement of the events of nature they bring to bear the standards of their own rules of conduct.

If we make a big jump forward in social development from the Stone or Bronze Ages to an advanced stage of the Iron Age, however, we find the producers equipped with metal implements: spades, sickles, hoes and ploughshares on the land, and hammers, saws, pincers, files, etc. in the artisan workshops. The producers in possession of such productive forces can take the best advantage of them by working independently of each other. They thereby become private producers, evolving an increasing amount of specialisation of trades. Of course the greater the development of the division of labour, the greater the mutual interdependence. [14] But it is a very different sort of interdependence from the collective or communal one discussed above. Social relations come to be determined by the relations between the products, whereas before they were determinant of production. The division of labour and the commodity relationship take over from and dominate the relations between people. The producers and owners of individual products enter into a network of private exchanges. In this interplay of exchanges, the means of production and the products become private possessions which are traded as commodities. It makes little difference to the formal rules of the exchange relationship—taken singly—whether the exchange agents exchange products of their own or have obtained them in other ways. In the process of exchange, the products of labour count as values differing in quantity only. The values must be agreed by their owners as being equal in order for the change of possessions to count as ‘exchange’. The property of both owners—counted in terms of value—must come out of the deal unimpaired.

So instead of societies of production, we now have societies of appropriation, in which production is for the market and in which the nexus of society results from activities of exchange, i.e. mutual relationships of private appropriation. In this situation we find the previous relation of theory and practice reversed. The social practice is irrational in that people have lost control over the system in which they live. As commodity production and the division of labour continue to develop, the irrationality of practice increases further, while the mode of thinking of the people assumes the conceptual form which we normally associate with rationality. In Greek antiquity, for the first time in history, commodity production reached the stage of a monetary economy, which Engels classes as ‘commodity production fully grown’ and as the start of ‘the age of civilisation’. In the conceptual mode of thinking then developing, nature is conceived as an object world independent of man for the first time.

____

123

This combination of irrational social practice and rational theory of nature is peculiar to commodity production. It has persisted—with important political and social modifications—throughout various developmental stages and is still with us. Does it leave us any hope of combining rational practice with rational theory? If so, what would become of science as we know it today? The term ‘science’ represents the tradition of rationally controlled thought and knowledge of the object world from Greek antiquity onwards. It also represents a clear-cut division of intellectual labour from manual labour. This division was not characteristic of the communal modes of production preceding civilisation; and if we could bring into being a society which combined rational socio-economic practice and rational theory of nature, the fundamental separation of head and hand could not persist. But let us look at the structural features and historical origins of the vile mess we are now in, even as we glimpse at a better future. The emergence of reasoning in conceptual terms around 500 BC has sometimes been called ‘the Greek miracle’. And it is to this historical and logical phenomenon that we must turn, seeking an explanation for it on the basis of the anarchic social process of commodity production. But can we show that it is an alienated form of consciousness? It certainly possesses the idea of ‘the truth’, but has the idea of ‘truth’ itself emerged in history in possession of false consciousness, and is that consciousness necessarily false?

We are now approaching the heart of the argument, and I find myself falling naturally into technical marxist language. To help with definitions and to provide a summary of the argument to come—a sketch map—I offer the following summary of my position, succinctly put by George Thomson, on whose own arguments I shall draw below. The concept of ‘pure reason’ was formulated in classical Greece as a reflection of the relations of a monetary economy.

In this way, man, the subject, learnt to abstract himself from the external world, the object, and see it for the first time as a natural process determined by its own laws, independent of his will; yet by the same act of abstraction he nursed in himself the illusion that his new categories of thought were endowed with an immanent validity independent of the social and historical conditions which had created them. This is the “socially-necessary false consciousness” which on the one hand, has provided the epistemological foundation of modern science right down to our own day, and, on the other, has prevented philosophers from recognising the limitations which are inherent in their “autonomy of reason” in virtue of its origin as the ideological reflex of commodity production.

Thomson continues on the topic of ‘the illusions of the epoch’:

It is characteristic of the ruling class of each epoch of class society to regard the established social order as a product, not of history, but of nature. This

____

124

is what Marx and Engels called “the illusion of the epoch”. It corresponds to the concept of “socially-necessary false consciousness”, and it follows from the marxist principle that “it is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but, on the contrary, it is their social being that determines their consciousness”. . . These “illusions” are inevitably reflected in the philosophical and scientific theories of the ruling class. The world of nature and of man is interpreted on the basis of certain assumptions which are accepted without question as absolute truths, although in fact they are historically determined by the position of the given class in the given epoch. [15]

Turning now from the summary to the argument itself, what is the origin of the peculiar abstraction which lies at the basis of thinking in terms of timeless universals of the sort we find in Greek philosophy and in Galilean and Newtonian science, in particular that of inertial motion? My answer to this question is a marxist one: I do not look at the mind and the nature of thinking as the primary source of this abstraction but at the social process of commodity production. Long before it becomes a theoretical concept, this abstraction is operative in the exchange process of society. It originates in human action, not thought. It may be unusual to speak of ‘abstraction’ as a spatio-temporal reality, but this is not loose talk or a mere metaphor, any more than ‘abstract art’ is. Marx uses the expressions ‘commodity abstraction’ and ‘value abstraction’ quite deliberately and with great care in his analysis of the commodity in the opening chapters of Capital. The process of exchange is the source of the abstraction which permeates commodity-producing societies, and its influence extends to the formation of intellectual categories. The following sentence from Marx is a model for the process I wish to explore: ‘The social exchange process gives to the commodity which it transforms to money, not its value but its specific value form.’

This distinction—between the value of a commodity, i.e. the magnitude of its value, and the ‘specific value form’—was first made by Marx and is of cardinal importance to my argument. The magnitude of value and its determination concerns economics, while the form of value relates to the abstraction operating in exchange and hence to the abstract mode of thinking arising from it. I argue that, when exchange relations in society reach a stage where the creation of coined money is called for— which first happened early in the seventh century BC in Ionia—the abstractness of exchange begins to impose itself upon people’s mode of thinking in a way initiated by Greek philosophy. This, put in the briefest way, is my historical and logical explanation of the birth of philosophy in the Greek society based on slave-labour, and of the birth of modern science in European society based on wage-labour. To substantiate this view, three points have to be

____

125

established: (a) that commodity exchange is an original source of abstraction; (b) that this abstraction contains the formal elements essential for the cognitive faculty of conceptual thinking; (c) that the real abstraction operating in exchange engenders the ideal abstraction basic to Greek philosophy and to modern science.

On the first point, commodity exchange is abstract because it excludes use. During the time that a commodity is subject to a transaction of exchange, it must remain exempt from use. But while exchange banishes use from the actions of people, it does not banish it from their minds. The minds of the exchanging agents must be occupied with the purposes which prompt them to perform their deal of exchange. Therefore, while it is necessary that their action of exchange should be abstract from use, there is also a necessity that their minds should not be. The action alone is abstract. The abstractness of their action of exchange will, as a consequence, escape the minds of the people performing it. In exchange, the action is social, the minds are private. Thus, the action and the thinking of the people part companyin exchange and go different ways. In pursuing point (b) of our theses we shall take the way of the action of exchange, while for point (c) we shall turn to the thinking of the commodity owners and of their philosophical spokesmen.

The abstract character of the exchange process is due to the fact that while it is an action carried out with useful things, it is itself concerned with the non-use of them. The non-use has a positive reality. If it did not, commodity exchange could not occur: there would be no commodities, only useful things. The action of exchange occupies a definite and measurable duration of time, the time required by the exchange transaction. The exchange can only take place thanks to this absence of use lasting through time. It can be short or long, but we know with certainty that the period of the exchange was a period of non-use. It is equally certain that commodities were thought to be objects of use, or nobody would have bothered to exchange them (and confidence tricksters would be out of business). The banishment of use during the exchange is entirely independent of what the specific use may be and can be kept in the private minds of the exchanging agents. (Buyers and sellers of sodium chlorate might have gardening in mind or bomb-making.)

This somewhat tricky and tedious analysis is simply an attempt to penetrate the construction of the economic category of ‘value’, a category which always relates to use as a precondition but blots it out for the purpose of the act of exchange. Students of natural science are likely to be unfamiliar with the formal features of the concept of value and to suspect that I am making heavy weather of the obvious. I would make two points in reply. First, it is worth recalling that long and strange analyses are familiar in, say, topology, atomic physics, cosmology or endocrine physiology. Second, I am building rather carefully toward the crucial conclusion of my argument.

____

126

To return to the concept of ‘value’: it is a purely practical abstraction, really nothing more than an escape out of the contradictions between exchange and use—the transformation of quality for use into quantity for exchange. I am not at all concerned with questions in the academic discipline of economics—with how this quantity is determined for the exchange relations of existing commodities. I am trying to lay bare the features of the formal quality of ‘value’ as the category we require in the practice of exchange. My concern is to make absolutely certain that the abstraction it involves is original and primary, and is spatio-temporal at the same time that its antecedents are not already in the minds of people engaged in exchange. It can then be treated as a ‘real abstraction’ of primary social and historical origin, and I shall soon show its relationship to scientific abstractions.

The reason for exchange and use being separate activities is that they belong to totally different reference frameworks. Exchange is a transaction of purely social significance which affects its objects only in their social status as property of private owners changing possessions. In order that this social change can obey its appropriate rules, the assumption must be made that the physical status of the commodities remains unchanged while the social action is in progress. You can easily convince yourself of this when looking in a shop window at a garment or other object of use marked with a definite price. The object stands or lies there in the fictional state of remaining in the same immutable physical state during the whole time that the price does not alter. Not only is it not to be touched by an unauthorised person but even nature itself is supposed to be at a standstill in the body of that commodity and, as it were, holding her breath for the sake of this social business of man. (It is to the fact that nature does not hold her breath that we owe many of the bargains of ‘shop-worn’ articles and foods whose ‘shelf life’ is coming to an end.) This experience is apt to draw our attention to the important fact that the contradiction between exchange and use extends even further than into man's physical activities and includes spontaneous events of physical reality. The abstractness of exchange —or, more precisely, of the action of exchange—is an example of what we class in conceptual language as ‘non-empirical’. It is a feature of this—as with other non-empirical categories—that the abstraction of exchange can bear no trace of any distinguishing mark by which one historical moment and locality can differ from another. The exchange abstraction is characterised by complete indifference to time and place, although it has itself the reality of an occurrence in historical time and place.

And now to come to the heart of my argument. While the act of exchange casts this spell upon the physical status of the commodities and any material change in them, it is itself, nevertheless, a physical act dealing with the

____

127

commodities as material things, e.g. by moving them physically through time and space from one owner to another. (Sometimes the owner moves, as into a newly bought home.) This context contains the complete structure of the exchange abstraction. We have only to put it under a magnifying glass and analyse it in all its details to obtain the epistemological foundation of science in the ages of commodity production.

The real abstraction of exchange comprises the complete set of non-empirical form elements which, when translated into correct concepts, or rather, when correctly identified, provides the theoretical foundation of scientific thinking, both for ancient Greek philosophy and for modern science on its emergence in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Our main concern is with the latter, which developed in close historical association with modern capitalism and should by rights—as well as on logical grounds, as will be shown presently—be classed as bourgeois science.

First, however, let me stress the fact that the purely formal nature of exchange is the same for all acts of exchange throughout the epochs of commodity production. This is also stated by Marx:

No matter how long may be the series of periodical reproductions and antecedent accumulations through which the capital now functioning may have passed, it always retains its primal virginity. As long as the laws of exchange are upheld in every act of exchange, individually considered, the method of appropriation [of the surplus] may be completely revolutionised without in the least affecting the property right applying to the production of commodities. This same right remains in force no matter whether things be as they were at the beginning when the product belonged to the producer, and when the latter, exchanging equivalent for equivalent, could enrich himself in no other way than by his own labour; or whether things be as they are in the capitalist period when to an ever increasing extent social wealth becomes the property of those who are in a position to appropriate, again and again, the unpaid labour of others. [16]

This invariable form of exchange provides the chainwork of the social nexus. It also acts as the epistemological foundation of science as rational theory. I say ‘acts’, for this epistemological foundation is not itself as something existing in an ahistorical world of ideas where the theory of knowledge dwells; it is a collection of historical events, each occurring in space and time, as real as the actions of use which they rule out. It is only by virtue of their comparable reality that use and exchange exclude one another in time and space and that the whole abstraction occurs. It is for this reason, the banishment of use and the replacement of it by a new reality, that in the German language the system of exchange is sometimes spoken of as a ‘second nature’ (eine zweite Natur)—a nature of purely social reality and significance and of exclusively human understanding.

From the point of view of commodity production our entire social network is made of this ‘second nature’. I soon become aware of the dividing line between the ‘first’ and the ‘second’ nature if I take my dog with me

____

128

to the butcher's. How does he analyse the proceedings? He understands a great deal and seems to have very definite ideas of property, judging from the way he snarls at people whom he suspects to have designs on the meat he is allowed to hold in his mouth, ready to run home. But when I have to shout at him: ‘Wait! I haven't paid for it yet!’ his analysis and mine part company. He knows these bits of paper and metal: he has seen them before. He knows they are not for eating and that they carry my scent or the butcher's, but their meaning as money is not part of his world of nature. Of what does this meaning consist? First of all, its meaning has no existence anywhere but in our human minds, although it is not of a mental origin. Its nearest empirical embodiment is money—coins and notes. But is the paper or the metal an integral part of it? Which metal? Silver, copper, this alloy or that or the legendary gold? Neither these metals nor the paper of the promissory notes possesses the absolute physical immutability which the exchange abstraction demands. The issuing bank has to make up for the imperfections of the ‘first nature’ on the standards of the ‘second’ by pledging gratuitous replacement of coins and notes that have suffered wear and tear from their circulation. Money must be made of matter; mere thought money would not be accepted for payment. But it should not consist of any empirical stuff; it must be real but non-descript. Because such a substance does not exist, we have to make out with aids from the first nature as second-best. (The word ‘substance’, incidentally, was not chosen at random. I want to return to it later.) [17]

The whole of this physical act of property transfer through exchange calls for close scrutiny. Each of its features has a constitutive role to play in the formation and historical genesis of the conceptual mode of thinking which we call the 'scientific' view of nature. For example, in this transfer of commodities separated from use, time and space take on a different aspect: they become continuous and homogeneous extensions. In a relatively short essay I can only assert this and the other formal features of the commodity exchange abstraction. The detailed analysis is published in my book on ‘Geistige und körperliche Arbeit’ (Intellectual and Manual Labour). The immutable and non-descript nature of the commodity requires us to probe into its materiality. This aspect is its substance, while the properties of its use-value adhere to it as its varying accidents. There would also be the question of the form of exchangeability of the commodities between owners. In their relationships of exchange they assume a solipsist attitude: only their own private thoughts on use-value have meaning and reality to them. The relationship of ownership is also mutually exclusive in each of their minds. There is also a principle of pure mathematical reasoning involved in commodity exchange. The equivalence of values in the exchange calls for changes in the mode of quantity when goods of different dimensional measurements are involved. Their mode of absolute quantity seems definable only by saying that one commodity is greater or smaller than, or equal to,

____

129

another. The abstract quantity emanating from the postulate of equivalence is no longer an entity which one could measure but an abstractum allowing for nothing but pure thought. There are also features of atomicity and of strict functional causality involved. To make my argument completely convincing, it would be necessary to spell out the analysis of each of these formal features of the commodity exchange abstraction and their relationship with scientific reasoning.

I have chosen the concept of inertial motion in the Galilean method of modern science as a test case for the historical account of a specific theoretical instrument of science. For this purpose, I shall take the following description of the commodity movement as it forms part of the exchange abstraction, and indeed sums it up: The commodities describe a pure linear movement through abstract—that is, empty, continuous and homogeneous— space and time as abstract substances which thereby suffer no material change and which are capable of none but quantitative differentiation. The affinity of this description to the Galilean concept of inertial motion is so close that it is impossible to brush it aside and ignore its consequences. The most weighty of these is the non-empirical character of the pattern as a whole.

However, there appear to be discrepancies as well. Most important among these is the lack of a reason why the commodities should, in their capacity as abstract substances which are not subject to material change, continue to move indefinitely. The crucial analogy to inertial motion seems not to keep moving for long, and if it comes to a halt, so does my argument. Let us take money as an example and see if we can keep it in motion. At the butcher’s my money moved no further than to his till. It is perfectly true that, in all cases of what Marx calls ‘simple commodity exchange’, money does not move in a continuous and endless way. Indeed, if it is used for hoarding it might end its course at rest in a stocking or in Silas Marner’s iron pot. But in focussing on these particular cases, we miss the general case, just as a physicist would fail to understand inertial motion if he saw only objects which were subject to friction or gravity. If we think of money as endowed with the function of capital, the movement of my coins will not end in the butcher's or any other salesman's till. In a capitalist economy money must move continuously or it will not retain the substance of its nondescript value. In capitalism money will not cease to move until the final end of money itself. Recalling our general historical framework, we should remember that the rise of modern science coincided with the rise of modern capitalism, and it is surely appropriate to associate Galilean dynamics—which was central to the specific features of seventeenth-century mechanics—with the triumph of capitalism. The power of movement emanating from this new science permeated that epoch—even into painting,

____

130

architecture and music.

But why should the circulation of capital be associated with the observance of movement in a straight line and at even speed? Surely this is an interpolation of Galilean invention but one that is fully justified since irregularities of the movement could only spring from the world of use which is banished from exchange. The assumption that the movement be in a straight line and of even speed has important methodological implications in yielding a concept of inertial motion fully amenable to mathematisation. By purifying the concept of all heterogeneous factors, inertial motion assumes the importance of being the absolute minimum of what constitutes a natural event—a movement which takes place while all of physical nature stands spellbound and still. And this minimal event has the quality of a pure conceptual thought, since it is not truly an event in real nature but a mathematical abstraction. It was in this capacity of elementary or minimal form of movement that Galileo used his concept of inertial motion as the basic means for constructing mathematical composites in regard to observable phenomena of movement—for example, the ballistics of cannon balls, which he proved to be nearest to parabolas.

I very much hope that the terms in which the concept of inertial motion have been presented compellingly recall those which characterised the suspension of the rest of nature during the commodity exchange process. But even with all this similarity and even structural identity ‘in the bag’, there remains the important difference that while the commodity exchange abstraction refers to a social reality in time and space, concerned with action and expressing the form of the economics of commodity production, Galileo’s inertial motion is a purely intellectual abstraction concerned with a logical ideal and aimed at the understanding of namre. How is it possible to bridge this gap between being and thinking and between such discrepancies of reference?

The link through which the commodity exchange abstraction is conveyed to the thinking mind is coinage. I want to relate the social being of monetary economy to what I said earlier about ‘substance’ when I was discussing the abstract or non-descript yet real matter from which money ought to be made. It was perfectly clear then that the insistence on the correct description of 'money-matter' would have led to a pure concept—that concept of ‘substance’—as the only adequate designation of ‘money-matter’. The first to arrive at a near identification of this abstract matter was the Greek philosopher Parmenides (about 520 BC) in his concept of ‘the One’ and ‘that which is’, that which alone has reality and constitutes the real substratum to all changing sense appearances. In later philosophy the concept of ‘substance’ was adopted instead and described by Kant, for instance, as the remaining element (das Beharrliche) in all appearances, one which neither increases nor diminishes in quantity. As to economists, commodities are composites of exchange-value and use-value; thus to philosophers all

____

131

objects of cognition are composites of substance and accidents (sense-qualities).

None of the philosophers using this or other of the abstractions due to exchange claims to have himself formed these concepts. Parmenides tells us how he had his concept revealed to him by the goddess Dike; Plato relates the ideas to a pre-existence of ours before birth; Kant to a transcendental synthesis a priori. These conceptual identifications of the non-empirical exchange abstraction and its elements are invading our consciousness ready-made. They are abstract before we know of them, products of our actions but hidden from our minds. Marx makes the same point when he says that the abstract constitution of value, into which (as he puts it) ‘not an atom of nature enters’, can never find an identical representation. This is because, within the network of exchange, it only expresses itself by the irrational equation with the use-value of another commodity. The tie-up of money with one or other use-value on the one hand, and one or other metal as a substrate for its function on the other, is thus inescapable but only within the market. [18]