György Lukács and Hungarian culture is a huge subject. All I can really do on this occasion is to throw some light on certain of its aspects which, in my opinion at least, have not been given the attention they should have by Lukács scholars either in Hungary or in other countries.

My starting point is a simple question: was György Lukács a thinker in the Hungarian tradition, or a German philosopher who happened to live in Hungary? This question may seem absurd to some, and superfluous to others, after all the whole world is aware that important indeed facts and periods in Lukács’s life were undoubtedly closely linked to Hungary (at the least also to Hungary), besides Lukács’s life’s work, in the eyes of Marxists and non-Marxists alike, is of international significance, of a standard that gives it international importance. The question is not absurd all the same since it is well known that Lukács was also part of the German philosophical tradition, he wrote his principal works in German and, what is more, he spent a great deal more time and effort on German than Hungarian literature. His life’s work can therefore also be regarded as part of German culture. Nor must it be forgotten that Lukács, the scion of a Budapest Jewish haute-bourgeoise family, already in early youth, at the turn of the century, sharply turned against the Hungary of that time and the gentry and pseudo-gentry interpretation of what being a Hungarian meant. All his life he emphasized his solitude as a thinker in Hungary, true enough also in Germany. Following a stay in Florence and Heidelberg in his student years, he lived in exile between 1920 and 1945, first in Vienna, then in Moscow, Berlin and again in Moscow. He was one of the leaders of the Association of German Proletarian Writers while in Berlin. There is therefore every reason to wonder how deep and how strong the threads were that

Text of a lecture delivered at the Institut Hongrois in Paris on May 10th, 1972.

[108]

109

tied Lukács to Hungary and Hungarian culture, that is in what sense one may look on him as a Hungarian writer, and on his work as something Hungarian culture can be proud of. This way of putting the question makes it clear, I think, that it is certainly not superfluous to examine what being Hungarian meant for Lukács, after all, if there were strong ties between Lukács’s work and Hungarian culture then the facts of Hungarian history and the characteristic features of Hungarian culture must be borne in mind when trying to understand Lukács's work even on a most elementary level. It seems to me to be one of the more serious weaknesses of the large and increasing literature dealing with Lukács that scholars are not able to understand the actual relationship between him and Hungarian culture. Even in Hungary there is still a great deal of uncertainty in this respect, few of the prejudices involved have been overcome as yet and research into the problem can be said to be in its initial stages only.

Perhaps Lukács himself is the right person to provide an answer. In 1970 he published a selection of essays written in Hungarian and on Hungarian subjects. 1 In a preface specially written for this volume in 1969, he described how he saw his relationship to Hungarian culture, and the way in which this developed. I should like to quote from this most interesting autobiographical piece at length, particularly where he refers to his origins and early oppositional attitude. “It is well-known that I was born into a capitalist family living in the ‘Lipótváros’ 2 in Budapest. I would like to say that since early childhood I was thoroughly dissatisfied with the Lipótváros way of life of those days. And since the business activities of my father brought us into daily contact with the city’s patrician and gentry officials, this rejection was automatically extended to them also. Consequently, I was ruled from an early age by oppositional sentiments against the whole of official Hungary. Corresponding to my immaturity this opposition extended to all domains of life, from politics to literature, and was obviously expressed in some kind of callow socialism.

It does not matter how childishly naive I consider it now, a posteriori, that I uncritically generalized this antipathy and extended it to all phases of Hungarian life, history and literature alike (with the sole exception of Petőfi) 3; it is certain that those views then dominated my way of thinking.

I Magyar irodalom, Magyarkultúra (“Hungarian Literature, Hungarian Culture”) Selected studies. Gondolat, Budapest 1970. 695 pp.

2 Lipótváros. A fashionable residential quarter in Budapest at the turn of the century, much favoured by the newly rich, largely Jewish bourgeoisie. Lipótvárosi indicated an ambiguous attitude that was common in those circles, on the one hand a nouveau riche excited desire to be noticed at all costs, on the other a fine sensitivity as regards culture which was rare in the traditional Hungarian ruling class.

3 Petőfi, Sándor (1823-1849). Hungary’s greatest and best known poet who played an important part in the 1848-49 Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence. He was killed in battle at the age of 26.

110

The serious counter‑force, the firm soil which then alone existed for me, where I could dig my toes in, was the modern European literature of those days, and it alone, with which I became acquainted around the age of fourteen or fifteen. I was touched primarily by Scandinavian literature (mainly Ibsen), the Germans (from Hebbel and Keller to Gerhart Hauptmann), the French (Flaubert, Baudelaire, Verlaine) and English poetry (first of all Swinburne, then Shelley and Keats); later Russian literature became important to me. It was out of these that I put together that force which was called to spiritually destroy the Jewish and gentry and pseudo‑gentry attitude. This not entirely accidental conjunction of circumstances led to my attempts at spiritual liberation from the spiritual servitude of official Hungary taking on the accents of a glorification of the international modern movement as against what I looked on as boundless Hungarian conservatism, which under those circumstances I identified with the entire official world of the time.” 4

Lukács then goes on to speak of two Hungarian contemporaries whose uncompromising moral attitude had a positive effect on him, describes his role in the Budapest theatrical life of the time and then continues: “it was at that stage that I discovered that important negative circumstance that I would take part in literature only as a theoretician and not as a creative author. The practical consequences of this lesson took me away from stage work itself; I began to prepare for theoretical and historic research into the essence of literary forms and turned towards scholarly and philosophic work. This again made me more acutely aware of the importance of the contradiction between influences from abroad, mainly German ones, and Hungarian life. It is hardly surprising that under those circumstances my starting point could only be Kant. Nor can it be surprising that when I looked for the perspectives, foundations, and methods of application of philosophic generalization, I found a theoretical guide in the German philosopher Simmel, not the least of reasons being that this approach brought me closer to Marx in certain respects though in a distorted way. My interest in the history of literature carried me back from the ‘great names’ of the present to those mid‑19th century scholars in whose writings I found methods of a higher order in the understanding of society and history. I deeply despised Hungarian theory and literary history from Beöthy 5 to Alexander 6. But important counterweights were to appear soon acting against this theoretical

4 Lukács op. cit. pp. 5‑7, Preface.

5 Beöthy, Zsolt (1848‑1922). Leading Hungarian literary historian of his time. His main work was a widely used textbook.

6 Alexander, Berndt (1850‑1927). Philosopher, Hungarian translator of works by, Descartes, Kant, Hume, Spinoza and Diderot.

111

one‑sidedness. Ady’s 7 volume Új versek (New poems) was published In 1906; in 1908 I read the poems of Béla Balázs 8 in Holnap 9 and within a short time we were linked by both personal friendship and a close literary alliance.” 10

This takes us to a decisive moment in Lukács’s life, decisive also when it comes to understanding Lukács’s work. The friendship between Lukács and Bela Balázs was important in itself, the more so owing to the fact that Balázs and Bartók closely cooperated in their work, but more important still was Lukács 's encounter with Endre Ady’s great poetic oeuvre, one of the great achievements of Hungarian literature early this century which is unfortunately almost inaccessible to those who do not read Hungarian. This encounter proved to be decisive for Lukács’s philosophy. It would be difficult to formulate this better than Lukács did himself: “My encounter with Ady’s poems was a shock, as one would call it today. It was a shock the effect of which I began to understand and to digest seriously only years after. My first experiment in the intellectual exploration of the significance of this experience occurred in 1910, but it was only much later, at a more mature age, that I was really able to grasp the decisive importance of my encounter with Ady’s poems for the evolution of my view of the world. Although I may be sinning against the chronological order of things, I believe that this is the place to describe this influence. To sum things up briefly, although the German philosophers, not only Kant and his contemporary followers but Hegel too—under whose influence I came only years later—appeared to be ideologically subversive, they remained conservatives in the great evolutionary questions of society and history; making peace with reality (Versöhnung mit der Wirklichkeit) was a basic tenet of Hegel’s philosophy. Ady’s decisive effect on me came to a head precisely because he never, not for a single moment, became reconciled to Hungarian reality and through it to reality as a whole as it then existed. A longing for such a view of the world had been alive in me since adolescence though I had not been able to generalize these feelings conceptually. I did not for a long time understand the clear expression of this attitude in Marx even after I had read him several times, and so I was unable to make use of him to oppose Kantian and Hegelian philosophy in a thoroughgoing way. But what I did not understand there struck my heart in Ady’s verse. Ever since I became familiar with Ady’s work this irreconcilability has been present in all my

7 Ady, Endre (1877‑19 19) Hungarian revolutionary poet of great impact, the first important figure in twentieth‑century Hungarian writing.

8 Balazs, Béla (1884‑1949). An important poet and dramatist, one of the great pioneer writers on film. Spent the inter‑war period in emigration.

9 HoInap. An anthology of modern Hungarian poetry published in 1908.

10 Lukács op. cit. pp. 7‑8, Preface.

112

thoughts as an inevitable accompaniment, although for a long time I did not become conscious of it to the extent that its importance would have required. To clarify these spiritual facts I may perhaps be permitted to quote a few lines of Ady which he wrote much later. In Hunn, új legenda (New Hunnish legend) he thus described this attitude to life, to history, to yesterday, today and tomorrow: Vagyok... protestáló hit és küldetéses vétó: Eb ura fakó, Ugocsa non coronat (I am... protesting belief and a veto with a mission ... ). It is peculiar that feeling about the world, which at the level then reached by me could hardly have been called an understanding of the world or a view of it, had a broad and deep transforming influence on the whole world of my ideas. It caused me to fit the great Russian writers, first of all Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, into my picture of the world as decisive revolutionary factors which shifted slowly but safely in a direction where the internal transformation of man stood expressedly in the focus of social transformation, where ethics became methodically more important than the philosophy of history. This became the ideological foundation of this feeling of the world, and in the last resort it grew out of my experience of Ady. This did not, of course, mean the total elimination of an objective socio-historical foundation. On the contrary, it was exactly at this stage of my development that French syndicalism began to influence me in a decisive way. I was never able to see eye to eye with the social democratic theory of those days, especially with Kautsky. My knowledge of Georges Sorel, thanks to Ervin Szabó' 11, helped me to develop the combined Hegel‑Ady-Dostoyevsky influence into a sort of ideology which I then felt to be revolutionary, and which made me oppose Nyugat 12, isolated me within Huszadik Század 13, and placed me in the position of an ‘outsider’ in the circle of my later German friends as well.” 14

The above makes it quite clear that the confrontation with Ady’s verse had a decisive effect on Lukács’s development, it was not, however enough in itself to ensure that he should think of himself as a Hungarian. In an interview given in 1966 Lukács said:

“Ady’s Új versek (New poems) really changed me. Speaking roughly, this was the first Hungarian literary work which allowed me to find my way home, the first I could identify with. What I now think of the Hungarian

11 Szabó, Ervin (1877‑1918). A left‑wing social‑democrat also known beyond the country’s frontiers. A leading member of the anarcho‑syndicalist opposition within the Second International.

12 Nyugat (“West’"). Founded in 1908, for thirty years the leading periodical of the Hungarian literary renewal.

13 Huszadik Szádad (“Twentieth Century”). The leading sociological journal in Hungary between 1906 and 1919. Contributors included Oszkár Jászi, Gyula Pikler and Bódog Somló. Karl Mannheim and Karl Polányi of the younger ones were later well known in England and America.

14 Lukács op. cit. pp. 8-9, Preface.

113

114

literature of the past is another question, and the result of long experience, At that time, I must admit, I felt no inner relationship with classical Hungarian literature, I was only creatively influenced by world literature, in the first place by German, Scandinavian and Russian literature, and also by German philosophy. German philosophy influenced me throughout my life, the moving experience which Ady afforded me did not essentially change this, it did not put an end to it and it did not take me back to Hungary. One could say that, at the time, the Ady poems meant Hungary to me” 15

Lacking a close link with Hungary, Lukács almost became German. He describes this in his 1969 Preface. “The experience of meeting Bloch (1910) convinced me that philosophy in the classical sense was nevertheless possible. I spent the winter of 1911‑12 in Florence under the influence of this experience, wanting to be undisturbed while working out my aesthetic theory as the first part of my philosophy. In the spring of 1912 Bloch came to Florence and persuaded me to go to Heidelberg with him where the environment was favourable for our work. What I have said so far must have made it clear that there was nothing keeping me back from moving to Heidelberg for a longer period, even permanently. Although I always preferred life in Italy to that in Germany, the hope of finding understanding was strongest. I went to Heidelberg without knowing for how long I intended to live there.” 16

Lukács spent 1915 and 1916 in Budapest as a member of the Auxiliary Services. At that time a circle of friends collected around him that led to an interesting experiment, the Free School der Geisteswissenschaften. To a certain extent however Lukács already felt isolated, even amongst his friends, owing to his revolutionary left‑wing attitude. Looking back Lukács writes: “Towards the end of the war a Group gathered in Budapest around Béla Balázs and myself, which soon grew into the ‘Free School der Geisteswissenschaften’. My earlier work no doubt played a certain role in its formation. It became important later thanks to the role played abroad by some of its members (Karl Mannheim 17, Arnold Hauser 18, Frigyes Antal 19, Károly

15 Conversation with György Lukács, in: Irodalmi Múzeum, Emlékezések I, Budapest 1967, p. 21.

16 Lukács op. cit. p. 13, Preface.

17 Mannheim, Karl (1893‑1947). Sociologist. Left Hungary in 1919, emigrated to Germany and after the Nazis came to power—to England. Taught sociology at the London School of Economics.

18 Hauser, Arnold (b. 1892). Art historian, has lived in Berlin, Vienna and London after emigrating from Hungary in 1921. Professor at the University at Leeds since 1951.

19 Antal, Frigyes (Frederick) (1887‑1954). Art historian. At one time on the staff of the Budapest Museum of Fine Arts. Emigrated to England in 1919. Was one of the foremost Marxist art historians of his time.

115

Tolnay 20); its influence in Hungary is often overestimated today for the same reason. It did not really mean anything important to me since it was essentially linked to a way of thinking and acting that I had already got over.” 21

Then the events occurred which proved to be the decisive experiences of Lukacs’s life, the 1917 Russian, and the 1918/19 Hungarian revolutions. Lukács, “by chance”, was caught by them in Budapest.

“The Russian revolution and its reverberating echo at home gave the first inkling of the contours of the answer. This road first opened up in front of me at home, but it was no ideologically conscious homecoming, it was not a necessary consequence of my evolution. Seen objectively and intellectually it was mere chance. (That it was not that from the aspect of my purely personal evolution, that it was help in this sense, a fate pointing towards the true path, is one of the facts of my life and as such outside the scope of this preface.) But even if my staying at home before and during the revolutions was purely chance as far as the immediate causes were concerned, it created entirely new contacts for my life which, having become conscious in the course of internal struggles lasting many years, produced an entirely new attitude in me.” 22

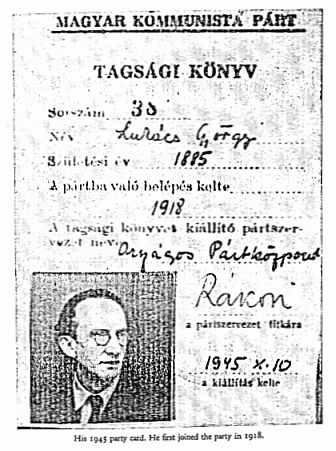

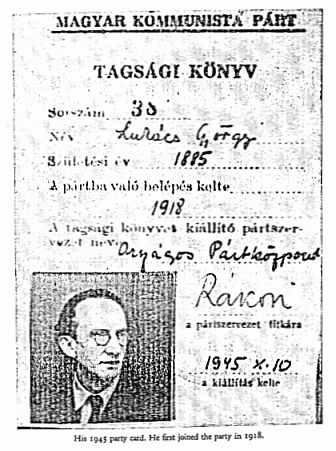

Lukács straightaway understood that a popularly based revolution could only be a socialist revolution in 20th‑century Europe. Not long after the foundation of the Communist Party in Hungary in 1918 Lukács joined it as one of its leaders. This meant giving up his past ways of thinking and a thorough study of Marxism. He became a People’s Commissar in the Hungarian Republic of Councils, in charge of cultural policy, that is when he found out that Hungary was not destined to be the country of revolutionaries without a revolution, that the best and the masses could be united in revolution in Hungary also. “The cultural policy of the Hungarian proletarian dictatorship was,” in Lukács’s words, “the first attempt to unite on the part of all those forces in Hungarian society that truly wished to progress and that sought a genuine renewal.” 23

I am inclined to argue that this decisive change meant that Lukács was clearly tied to Hungary by becoming a Communist, that his becoming an internationalist at the same time meant a strengthening of his ties to a particular nation. This is certainly not chance, but necessarily follows on the nature of what has been said.

And that though the Hungarian Republic of Councils was suppressed

20 Tolnay, Károly (Charles de) (b. 1899). Art historian of Hungarian birth, lives in Florence, Italy.

21 Lukács op. cit. p. 14, Preface; see also Emlékezések, pp. 31‑34.

22 Lukács op. cit. p. 14, Preface.

23 Loc. cit. p. 15, Preface.

116

and, in 1920, Lukács was forced to live in exile. He began to study Lenin seriously m Vienna, initiating a period in his thinking that lasted more than ten years. Lukács himself said that in the ’20s he had tried to reconcile a “right-wing epistemology” with a “left‑wing morality” producing a “messianic sectarianism.” It is most interesting that this “messianic sectarianism” was manifested in the first place in his philosophic views and in his attitude to international questions, as regards the problems of the Hungarian working-class movement, he supported the Landler 24 faction, as against Béla Kun, 25 and also in opposition to his own theoretical views. Landler’s more realistic ways of thought served as a basis for overcoming that “leftishness” which Lenin also criticized.

Following Landler’s death Lukács formulated the so‑called Blum‑theses 26 which saw the future of the Hungarian working‑class movement in a democratic dictatorship of the working class and the peasantry. Lukács’s theses were rejected by the party leadership at the time, and Lukács himself was removed from the position he held. But this failure did not put a distance between him and Hungary, but on the contrary, made the links closer still. Lukács said of the importance of the theses for his own development that it was here that “in my case a general theory allowing for further generalization grew directly out of a proper observation of reality, that is where I first became an ideologist who took his cue from reality itself, what is more from Hungarian realities.” 27

Lukács therefore was ready to consciously and finally accept his role as part of Hungarian culture precisely at a time when following his removal from the responsibilities of political office he tended to concentrate his work on German as well as English, French and Russian literary problems. I hope I will be forgiven for the longish quotation that follows, but it seems to be that Lukács’s own words best express what is involved here.

“The Blum‑theses put an end to my political career and took me away from the Hungarian party for many a long year. At the same time, as a

24 Landler, Jenő (1875‑1928). A lawyer and a leading member of the Hungarian social‑democratic movement. First Commissar for Home Affairs, then Commander in Chief of the Red Army during the 1919 Republic of Councils. Later one of the leaders of the Hungarian communist emigrants in Vienna.

25 Kun, Béla (1886-1939). One of the founders of the Communist Party of Hungary (1918), the leader of the Hungarian Republic of Councils (1919). After the victory of the counter‑revolution, emigrated to Austria and later to the Soviet Union. A victim of Stalin’s purges in 1939.

26 Blum‑theses. Draft report to the 2nd Congress of the Hungarian communist Party written by Lukács in 1928.

27 Lukács op. cit. p. 18, Preface.

117

direct consequence of the crisis, my theoretical and critical work as an aesthetician received a new impetus. I was able to take an active part in the struggle against literary sectarianism on the German and Russian fronts, I was able to lay down the theoretical foundations of Socialist realism, in uninterrupted, but, needless to say, concealed opposition to the Stalin‑Zhdanov views then prevalent. This took me to the 7th Congress of the Comintern, which came out with the first public statement summing up the popular front policy and at the same time reopened the door to the Hungarian party for me. When, after this Congress, the paper of the Hungarian popular front, Új Hang appeared, 1 became an active contributor right from the start, once again working with József Révai 28. We had been apart for a long time. It was there that, for the first time since I became a Marxist, I discussed Ady and the Babits of The Book of Jonah. 29 It was there that I attempted to criticise the false antithesis between urbánus 30 (urban) and népi 31 (populist) writers from the point of view of a true Hungarian democratic popular front. I wrote those articles as a Marxist communist, but these papers never centred on the opposition of Marxism and bourgeois ideology but on a united Hungarian popular resistance to the Horthy regime. This meant a break with the critical practice of Hungarian communists in which arguments expressed in Hungary were judged by Marxist standards. When arguing against the urbánus I pointed out the distortions caused in the Hungarian development of revolutionary democracy by liberal prejudices such as the rejection of radical land reform in the interest of the undisturbed capitalist development of large estates. These were differences between liberalism and democracy, and not between socialism and democracy, and both Révai and I always recognized and supported the spontaneous plebeian democratic faith of the népi writers and only reproached them for often expressing those ideas inconsistently (making concessions to reaction in opposition to the people). But I, for instance, showed that their ideology in some important respects was dangerous to Hungarian democratic evolution, even by Tolstoyan and not Marxist standards. In this way I joined the mainstream of the best traditions of Hungarian literature. Csokonai 32

28 Révai, József (1898‑1959). One of the leading theoreticians and politicians of the Hungarian communist movement.

29 Babits, Mihály (1883‑1941). Second only to Ady amongst the poets of the Nyugat group, editor of the review. Also wrote novels, essays and criticism. Jónás könyve (“The Book of Jonah”) is a confessional narrative poem on guilt and responsibility he wrote not long before his death.

30 “Urbánus”: an urban liberal‑anti‑fascist literary group which was indifferent and even hostile to the peasant literary movement.

31 “Népiesek”: radical peasant literary movement some of whose members blended social criticism with an irrationalist ideology.

32 Csokonai Vitéz, Mihály (1773‑1805). Hungarian poet of the enlightenment, author of a still popular comic epic, of sensitive lyrical poems and satirical plays.

118

and Petőfi, Ady and Attila József 33 all took this starting point with activities that grew out of the people’s attempts to determine its own fate. If Hungarian literary history and criticism—apart from exceptions such as János Erdélyi 34 of old, Ady later and György Bálint 35 in the Horthy era—did not proceed along this path, this does not throw doubt on the correctness of the way the question is put, nor does it lessen its rootedness in the life of the Hungarian people. Due to this radical change in my internal evolution, my return home in 1945 in no way looked like the coincidence to which I owed my presence in Hungary during the 1918 revolution. On the contrary, this was a fully conscious decision in favour of returning home against concrete offers made attracting me to places where German was spoken.” 36

Lukács’s self‑analysis must be looked on as decisive as regards his relationship to Hungary, and he clearly and unambiguously declared himself to be Hungarian. Following his return to Hungary he passionately threw himself into literary and cultural life and wrote a number of important papers that dealt with basic problems of Hungarian culture. Summing up this last, more than twenty years long period of his life, he said: “If I wished to characterize this whole period ideologically, I must point out that in addition to Ady the influence of the plebeian democratic nature of Bartók’s art (Cantata Profana) became stronger and stronger on me. I would of course give a false picture of the totality of my activities, including the part concentrating on Hungarian problems, if I made it appear as if Hungarian literary and cultural topics had then dominated my entire activity. This has not been the case. At the time of Új Hang I wrote my book about the young Hegel, after Liberation I produced The Destruction of Reason, and Particularity, later my aesthetics and I am now about to formulate the philosophical nature of social existence. The bulk of my ideological activities has all the time dealt with general philosophic problems. These must necessarily point beyond Hungarian reality. Not even a member of the greatest people on earth would be able to think philosophically (including of course thinking on aesthetics) merely on the basis of his own national experience.” 37

Every page of the volume of selected studies on Hungarian literature and culture bears out what Lukács says in the Preface. One soon discovers, looking through the volume, that Lukács’s critical and theoretical work is in

33 József, Attila (1905‑1937), Hungarian revolutionary poet, still the most influential force in Hungarian poetry.

34 Erdélyi, János (1814‑1868). A leading 19th‑century democratic critic, one of the first to popularize Hegel in Hungary.

35 Bálint, György (1906‑1943). A Marxist journalist and critic, one of the bravest and most talented members of the literary left in the Horthy‑age.

36 Lukács op. cit. pp. 8‑19, Preface.

37 Loc. cit. p. 20, Preface.

119

accord with his self‑analysis. All I should like to do now is to draw attention to certain particularly interesting aspects. In 1908 young Lukács still wrote that Ady “had no need of tradition, that he did not accept any Hungarian values or join any existing trend” and that it was precisely to this that he owed his greatness as a poet. 38 In another article Lukács said that it was a tragedy that Ady was Hungarian. 39 In 1909, in a book on the history of the modern drama, he opposed the vulgar interpretation of the “international modern movement” and spoke of Mihály Vőrösmarty’'s fairy play Csongor és Tünde 40 as the “most alive, and perhaps only genuinely organic Hungarian play.” He argues that “"it was not chance, not a meeting of fortunate outside and inner circumstances that proved successful in this instance, but the conscious and artistic welding of Hungarian folk‑humour and the mood and techniques of Shakespearean comedy. The main reason why Hungarian fairy‑comedy ceased to be organic later was that it lost its there present relationship with Hungarian life.” 41 In an article on Ady published the same year he considered that the peculiar character both of Ady and of Hungarian radicalism was to be found in the fact that “there is no Hungarian culture which one could join, and since the old European one does not mean anything from this point of view, only the distant future can produce the dreamt-about communion for us.” Looking ten years ahead, he predicted 1919 saying that Ady was “conscience, and a fighting song, a trumpet and standard around which all can gather if there should ever be a fight.” 42 That same year, writing about a volume of short stories by Zsigmond Móricz 43, Lukács said: “One can only speak of this volume with genuine joy. It contains true Hungarian short stories, and Hungarians in the simplest, most common and most used up sense of the term.” 44 Reading this one might well wonder whether Lukács did not somewhat exaggerate in his Preface quoted above when he said that he had no “inner” relationship to Hungarian literature at that time.

In 1918 when Mihály Babits accused Béla Balázs and Lukács of being “German”, Lukács proved that Babits wanted to protect Hungarian literature against philosophic “depth”. Lukács showed how retrograde the Hun-

38 Loc. cit. p. 26, “Kosztolányi Dezső” (1907).

39 Loc. cit. pp. 34‑36, “A Holnap költői” (The Poets of “Holnap”), 1908.

40 Vörösmarty,Mihály (1800‑1855). Hungarian poet, wrote historical epics and lyrical verse showing a powerful romantic imagination and great beauty. Csongor és Tünde (“Csongor and Tünde”) is a philosophical play in verse based on a fairy tale, written in 1831 and still popular today.

41 Lukács op.cit. p. 38, A magyar drámáról (“On the Hungarian drama”), 1909.

42 Loc. Cit. p. 45 and 51, AdyEndre (“Endre Ady”), 1909.

43 Móricz, Zsigmond (1879‑1942). One of the great Hungarian 20th‑century novelists, founder of the populist school.

44 Lukács op.cit. p. 60, Móricz Zsigmond novellás könyve (“Zsigmond Móricz’s volume of short stories”), 1909.

120

garian “stiff upper‑lip” and “nil admirari” spirit was. Lukács asks “Whether one can say that there will be and there must not be any philosophic depth in Hungarian literature in the future, just because there was none in the past?” “Has the Hungarian soul reason to be afraid of depth?” 45 It is dear that Lukács at that time was already fighting the same fight as Ady and Bartók, the leading spirits in Hungarian cultural life.

Lukács without his relationship to Hungarian culture: the picture would be pretty anaemic even discussing the 1920s. In 1925, for instance, only two years after History and Class Consciousness appeared, right in the middle of his “Messianic sectarianism” Lukács published a short article on Mór Jokai 46, who dominated post‑1867 Hungarian literature. Lukács argued that Jokai “wanted no more in 48 than came true in 67.” “Jokai’s narrative style” Lukács goes on, “is still fully interwoven with the old Hungarian manner of telling a tale, which is humourous and imaginative and anecdotal, a style that only loosely links up events. As against his contemporaries, Zsigmond Kemény 47 and József Eötvös 48 who insist on forcing the style of the foreign novels of the time on nascent Hungarian prose, Jokai’s style organically grows out of the Hungarian life of his own period. In this respect Jokai’s prose can justifiably be compared to Petőfi’s prosody. Though it is true that this manner of writing is full of loose and undisciplined elements ... this was nevertheless the only road along which Hungarian narrative prose could progress right up to Zsigmond Móricz, while the artificial prose of his contemporaries remained an episode in the development of Hungarian literature.” 49

Lukács remained true to the simple principle that “the true greatness of poets rests in their being welded to the life of their nation” 50 all his life, what is more, in his own work he put this principle into practice in an increasingly consistent manner. That is why his internationalism has nothing to do with cosmopolitanism, and that is why his criticism of the népi and urbánus movements of the thirties is still valid today. He explains the real

45 Loc. cit. pp. 133‑134, Kinek nem kell és miért Balázs Béla költészete (“Who don’t want Béla Balázs’s poetry and why”), 1918.

46 Jókai, Mór (1825‑1904). Hungarian romantic novelist, immensely popular in his lifetime in Hungary and abroad; still widely read today. His collected works appeared in 100 volumes.

47 Kemény, Zsigmond, Baron (1814‑1875). Novelist, journalist, politician, author of important historical and social novels as well as essays and political journalism.

48 Eötvös, József, Baron (1813‑1871). Novelist, journalist, politician, an important figure of Hungarian political life, author of realist novels that were widely read and published even in Victorian England.

49 Lukács op. cit. p. 150 and 151, Jókai, 1925.

50 Loc. cit. p. 158, Ady, a magyar tragédia nagy énekese (“Ady, the great bard of the Hungarian tragedy”), 1939.

121

achievements of both as the effect of the 1919 Hungarian revolution, and that, it seems to me is interesting even in the context of world literature. By and large be considered the népi movement to be the more important of the two, precisely because of the close links with the peasant masses and the life of the people. In 1947 he read an article in which népi writers were viciously slandered, while writers of Jewish origin were praised to the skies in an unprincipled way. Lukács proved that the author applied two different standards in an unprincipled way. “.. . this method and attitude have their own social background ... To put it briefly, what is involved is the literary and cultural role of the so-called Lipótváros. Béla Zsolt 51 describes its style with great love, applying positive standards only, allowing at the most for certain tragic features. But that social and national lack of roots which the Lipótváros culture meant for Hungarian writers of Jewish origin at the time (i.e., at the turn of the century) only rarely grew into a genuine tragedy. The break with genuine Hungarian folk culture bred the false extremes of snobbery and literary prostitution; there were of course writers with a happier temperament who preserved their human and literary integrity protected by the hedge of a sort of narrow specialization. But one cannot, without applying two separate standards, argue that tragedies like János Vajda’s 52 or Lajos Tolnai’s 53 took place, not to mention Kálmán Mikszáth 54. It is Ady’s great merit, and that of the Nyugat‑revolution as a whole, with all its limits and contradictions, that they started to demolish these barriers. The real work of demolition was however done by the class struggles of the counter‑revolutionary period, and by népi literature which arose as part of them. Until then there had only been a writer here and there. . . who rose above the dilemma of snobbery and literary prostitution, the counterrevolutionary period produced a new type of writer, liberated from the Lipótváros, not great masses of them perhaps, but respectable numbers nevertheless, and of a quality that commanded respect... and... in the case of more than one outstanding writer alive today, that ideal and artistic, meaningful and formal engagement in the great social and national problems of the Hungarian people which destroys every difference of origin in the eyes of all unprejudiced men and women became part of their flesh and blood—and helps to pull out the ideological roots of antisemitism. . .”

“At the time of the first revolutionary uprising of the Hungarian

51 Zsolt, Béla (1895-1949). A leading Hungarian liberal journalist of the thirties.

52 Vajda, János (1827‑1897). Hungarian poet and journalist, a forerunner of modem city‑life poetry.

53 Tolnai, Lajos (1837‑1902). Novelist, a bitter critic of contemporary Hungarian life, especially the lesser nobility and local administration.

54 Mikszáth, Kálmán (1847‑1910). Novelist and journalist, one of the great figures of Hungarian fiction still very much read today.

122

nation Jewry had only reached a stage of development where it could provide thousands of brave soldiers to hosts fighting for freedom. 55 The social backwardness of Hungary made it impossible for this fight for freedom to become manifest in Jewry in an ideological form. Heine... was the true representative poet in Germany, a more developed country (i.e., at the middle of the 19th century). Nothing like that could happen in the sultry atmosphere of the 1867 Ausgleich and of the Lipótváros pseudo-gentry ghetto. The breeze of the revolution was needed to bring that about. That is what started with Nyugat, and was continued, at a higher level of social development, in the period between the two world wars. As Marx rightly says: ‘The soil of counterrevolution is also revolutionary’.” 56

There are not many in Hungary who could criticize Lipótváros culture with greater justification and therefore with greater persuasive force than Lukács who was born and bred in the Lipótváros, but who became a revolutionary and found his way home to his country in that way.

Writing of Ady’s importance and influence in 1969 Lukács said: “Those who were not satisfied with the (1867) Ausgleich, one could say, did not consider the situation from a specifically Hungarian view.” 57 The passages I have quoted indicate how one ought to interpret this sentence. Lukács continues: “I have not lost touch with Ady, not even for a day, since reading Új versek more than sixty years ago. This is part of the story of my life, and, without wishing to exaggerate my importance, I cannot really consider myself as typical of Hungarian development.” 58 Allow me to express my suspicion that Lukács, in this case, did not use the term “typical” in the sense of his own aesthetics but, as often happens with vulgar critics, in the everyday sense of the word, his language would have been more exact if he had said “average”. I am convinced that, taking the term as used in aesthetics, Lukács was a most typical manifestation of Hungarian culture, though he was of course no more average than Ady, Bartók or József.

It is certainly worth investigating how Hungarian culture managed to accomplish a whole series of achievements of international significance in the 20th century. This seems to me necessary for a proper understanding of the achievement itself. All that I have said is of course no more than one of the necessary preconditions of asking the right questions. This is true even as regards a proper understanding of Lukács’s work.

55 Reference to the War of Independence, the armed conflict in 1848-49 between the Hapsburg forces and Hungary that was finally crushed when the Czar sent in troops which overpowered the Hungarian Army. Thirteen Hungarian Army generals were executed by the Austrians on October 6, 1849.

56 Lukács op. cit. pp. 443-444, Egy rossz regény margójára (“Marginal note on a bad novel”), 1947.

57 Loc. cit. p. 606, Ady jelentősége és hatása (“Ady’s significance and influence”), 1969.

58 Loc. cit. p. 609.

SOURCE: Tőkei, Ferenc. “Lukacs and Hungarian Culture,” The New Hungarian Quarterly, no. 47 (vol. 13, Autumn 1972), pp. 108-122.

“Lukács and Hungarian Literature” by Ivan Sanders

“The Importance and Influence of Ady” by György Lukács

Georg Lukács’ The Destruction of Reason: Selected Bibliography

Home Page | Site Map

| What's New | Coming

Attractions | Book News

Bibliography | Mini-Bibliographies

| Study Guides | Special

Sections

My Writings | Other

Authors' Texts | Philosophical Quotations

Blogs | Images

& Sounds | External Links

CONTACT Ralph Dumain

Uploaded 3 March 2016

Site ©1999-2023 Ralph Dumain